The Davos Blocks

Note: The Stevenson Society of America wishes everyone an enjoyable cartoon-themed Winter Carnival with the reprinting of this column by Mike Delahant and first printed in the Enterprise on Sept. 1, 2022.

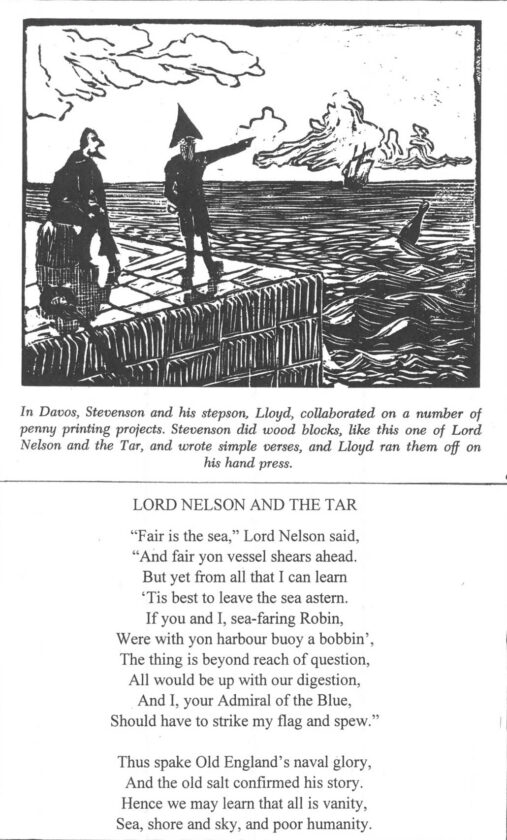

From the Saranac Lake News, Feb. 8, 1917: “Mr. Osbourne also spoke of the wood blocks which were carved by R.L.S. and are now, through his stepson’s gifts, on exhibition at the Stevenson Memorial. He told how they were made at Davos, Switzerland, when Mr. Stevenson was ill and exercised his indomitable spirit in cheering himself and the youthful printer (Mr. Osbourne himself) with his toy press.”

Lloyd Osbourne had been lucky. Of all the kids in the world in his time, he was the one who got to be Robert Louis Stevenson’s sidekick, the one who had the creator of Long John Silver for friend, mentor and playmate. All of Stevenson’s friends could tell you about the forever boy inside that unspeakably slight frame, most notably J.M. Barrie. For 14 years, Lloyd would be that soul’s favorite companion, with the exception of Lloyd’s mother, until death bid them all part.

The great gamble RLS had bet on in the summer of 1879, to go alone all the way to California, in adverse circumstances, to find and somehow marry Mrs. Fanny Osbourne, had paid off with unexpected dividends for future generations of readers. The stimulus provided by his new and recently divorced wife and especially Lloyd (though his father’s money was still important), turned out to be the catalyst that shot Stevenson’s career into high gear. It’s no coincidence that this writer’s most prolific period began with his return to Scotland from America, with Fanny and Lloyd, in the summer of 1880.

Stevenson’s year-long quest in the New World had almost killed him, in all seriousness, and he would certainly have died there as a trespasser on a goat ranch had not luck, or fate, or divine providence or something else intervened. The overall experience had exacted a toll on the invalid’s precarious health and that explains his presence for the next two winters at a health spa called Davos in Switzerland, the Magic Mountain of Thomas Mann’s famous novel.

The toy press and woodblocks mentioned above hail from this period. Lloyd had brought his press into the Alps all the way from California. The 12-year-old entrepreneur used it to go into business by printing out menus, concert programs, invitations and announcements for the Hotel Belvedere, their first winter’s quarters in Davos. To Louis, Lloyd’s press presented itself as something new to exploit on behalf of his unquenchable creative instincts. Lloyd granted Louis partnership in the firm but the name of it remained Samuel Lloyd Osbourne and Co. Lloyd’s new colleague wasted little time submitting his first just for fun group of verses given the title “Not I.”

During this Davos period, the creative cross-currents in Stevenson’s head were swirling mightily. “Treasure Island” was just one of several concurrent projects along with churning out magazine work for Cornhill, starting the ever popular collection of poems called “A Child’s Garden of Verses” and finishing “The Silverado Squatters,” the true life account of vagabond newlyweds who transformed an old mine on a mountainside into their honeymoon suite. But that’s another tale from the unusual lives of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Louis Stevenson.

At the height of this unprecedented pen pushing activity, Louis discovered that his partner’s press could serve as an escape mechanism from all that cerebral activity. Drawing and sketching for diversion was nothing new to RLS but he had never toyed with woodcuts–designs carved in relief on small blocks of finely grained wood that get inked and pressed onto paper to make images. Having commissioned suitable blocks for the task from a local woodcarver dying of consumption, Louis drew out his pocket knife and began to carve. He cut out crude but effective scenes to go with verses he made up which together form themes. Called moral emblems, they weren’t new but more like old, stale forms of moral instruction, primarily for children, that had peaked in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Leave it to Louis to radicalize his approach to the genre and stamp his creations in standard Stevensonian style which included unrestrained parody of convention. Some of his motifs are carried over from other projects like the hero’s journey, duality, the sea and adventure, murder, greed and pirates. Professor Wendy R. Katz of St. Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, had this to say in her article, “Mark, Printed on the Opposing Page: Robert Louis Stevenson’s Moral Emblems”:

“Stevenson’s Moral Emblems are shot through with ironic humour. Respectability is linked to piracy and then to hypocrisy while pragmatism and commercial enterprise are aligned with slothfulness and ultimately with cowardice. Prayerful thanksgiving gives way to unsettling greed, and murderous rage to digestive indisposition. Whatever personal factor contributed to this ironic spirit, determinants of a cultural or historical nature were also at work. Indeed, insofar as Stevenson’s emblems tarnish the sheen of convention, they are quite in keeping with the new spirit of resistance and rebellion found in late nineteenth century children’s literature.”

For RLS, cutting around the lines he had drawn on the blocks was just what the doctor had ordered. Said the woodcarver:

“I cannot tell you what a godsend these silly blocks have been to me. When I can write no more and read no more and think no more, I can pass whole hours engraving these blocks in blissful contentment.”

Lloyd put ink and press into action with each new woodcut Louis completed and “thus Moral Emblems came out; ninety copies, price sixpence. Its reception might almost be called sensational. Wealthy people in the Hotel Belvedere bought as many as three copies apiece. Friends in England wrote back for more. Meanwhile the splendid artist was assiduously busy. He worked like a beaver saying that it was the best relaxation he had ever found” (Lloyd Osbourne, preface to Scribner’s 1921 edition of “Moral Emblems.”)

The Davos Press ran steadily until the summer of 1882. Then it broke and defied repair and has since had a home for many years at Lady Stair’s House, a.k.a. the Writer’s Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland. The creation of moral emblems by RLS was thus confined to the crucial Davos period of his career, the first great turning point, and they have found their own unique corner in the rich, vast, and varied legacy of Stevenson’s literary output.

“I mention the blocks for a special reason,” said Lloyd Osbourne at the Saranac Lake Free Library in the winter of 1917. “I am very happy to think they have come at last to Saranac Lake and I have a hope that many who are in this town under circumstances not unlike those that surrounded Mr. Stevenson may gain some inspiration and encouragement from a study of them and from some reflection on the spirit that urged their creation.”