The complexities of successful leadership

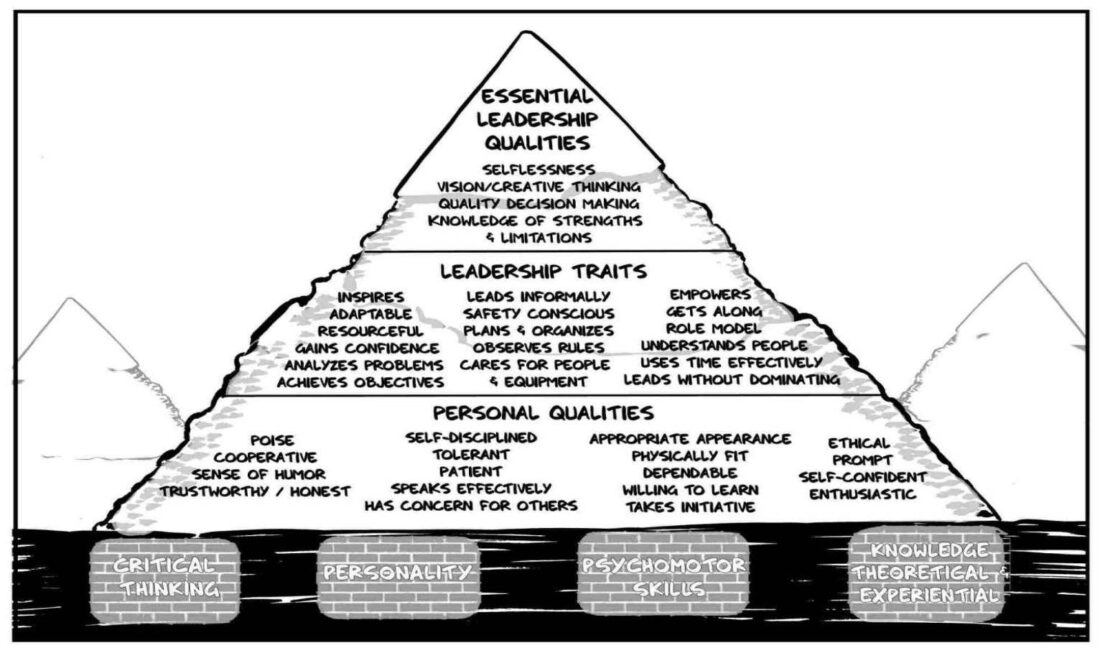

This graphic shows some of the qualities desirable for outdoor leaders, from Jack’s text, “The Backcountry Classroom.” (Provided photo — Jack Drury)

“Leadership and learning are indispensable to each other.” — John F. Kennedy

Everyone plays a leadership role at one time or another. Don’t think you don’t. We do it in numerous ways. If you’re a parent, a boss, a teacher, a coach or do anything to help a group get something accomplished, you are a leader. However, you have a better chance of being a successful leader if you realize it and try to be the best leader you can. But you can only learn so much about leadership in the classroom. You need to get out and work with a team of people to really learn leadership.

For example, team sports are a great place to practice leadership. The captain linebacker of the high school football team not only calls the defensive plays but has to pat the defensive tackle on the butt and convince him to keep working hard despite his exhaustion, get the safety who got beat for a touchdown to put it behind him and get the player who is convinced that they can’t win to change his mind or get off the field.

The outdoors provides a similar environment. It’s why NASA sends astronauts on National Outdoor Leadership School 10-day wilderness expeditions — to develop leadership, teamwork and decision-making skills in a challenging and unpredictable environment … just like outer space … sort of.

A fine example of real-world leadership was during a month-long fall trip when a young lady named Kate was the Leader of the Day. She was petite yet strong. She was also bright and oozed leadership potential. She was a bit younger than her peers but wasn’t afraid of taking on the role of leader. She was tasked with leading her group to the top of Donaldson Mountain, one of the Adirondack’s 46 highest peaks. But it wasn’t just a tall mountain; we were bushwhacking as opposed to taking a herd path, which didn’t exist in those days on the mountain’s western slope. Bushwhacking through the thick, nearly impenetrable forest was an exhausting and disorienting battle. We had to fight our way through dense undergrowth, intertwined spruce and fallen trees piled on one another like giant pick-up sticks. Every step demanded brute effort and constant vigilance, as progress slowed to a crawl and navigation became a mental and physical challenge. It tests the mettle of even the most experienced outdoor leader.

As leader, Kate wasn’t at the front of the line. She had a scout that she monitored to make sure he was heading in the right direction while she floated among her fellow students making sure they were drinking plenty of water (and refilling their water bottles once empty) and eating plenty of GORP (good old raisins and peanuts). Also, making sure each hiker could always see the person in front of them and the person behind them, yet weren’t so close as to get slapped by branches as they hiked through the thick brush.

We started hiking around 5 a.m., and after six hours, were close to the mountain’s ridge where there was an easier herd path to the summit.

As the group struggled following the brook up the mountain, suddenly it forked. Kate huddled with her best map readers but failed to figure out exactly where they were. Which stream would lead to the ridge? Kate decided to send a scout up each stream … a good decision. She failed, however, to tell them how long to go before heading back … a not-so-good decision. As a result, one scout fought the thick brush over the stream for five minutes and turned around, while the other, fighting the same thick vegetation, went up 20 minutes before turning around. We lost nearly an hour of time before Kate decided on the route, and we headed up toward the ridge.

You may think, what’s an hour? There’s plenty of daylight. True enough, but daylight is a finite resource when outdoors, especially in the fall. Being caught in the wilderness after dark can be a recipe for disaster as visibility becomes limited to the power of your flashlight, as the temperature drops and as an easy hike turns into a potential life-threatening situation.

We eventually summited and had memorable views. Kate took great pride in leading the group up through the challenging terrain. How challenging was it? The students decided it was easier to take the herd path nine miles back to camp rather than bushwhack two-and-a-half miles back through the thick terrain. We ended up getting back to camp at 10 p.m., hiking over two hours in the dark.

Kate rose to the occasion and learned, through experience, what it was to be a leader. She wasn’t perfect, but none of us are. We’re human.

A good leader is reflective upon their strengths and weaknesses. My good friend and fellow student at SUNY Cortland, Tom Buchanan, became president of the University of Wyoming. He seemed to be well-liked and respected. One time I asked, “What’s the secret to being a successful president?” He said, “There’s no secret, just don’t be afraid to surround yourself with people who are smarter than you.” For most of us, that should be easy.

The difference between leadership and good leadership was demonstrated by an older student of mine struggling to balance the challenge of getting the task done with keeping people happy. At the end of the day, as we finally made our way into camp, he said, “You know, leadership is thorny stuff. I was a construction crew foreman for years. When someone wasn’t getting the job done, I’d just hit’em alongside of the head with a two-by-four. Now I see now that leadership is a lot more complex than that.”

Indeed, it is.