Local lawmakers want to expand the definition of ‘affordable housing’

State, local officials: Middle-income people need housing, too

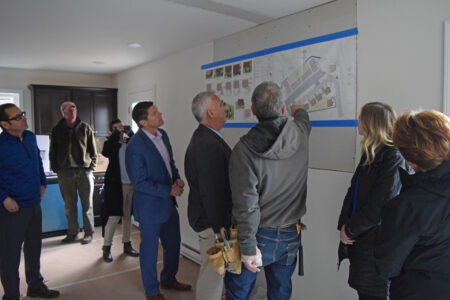

- At right, state Assemblyman Matt Simpson, R-Horicon, talks about the Fawn Valley housing development with Pat Fricchione, CEO and general partner at Simplex Homes, at the development on Monday, Oct. 17. Simplex is supplying the modular homes and townhomes for Fawn Valley. Assemblyman Billy Jones, D-Chateaugay Lakes, is seen center. (Enterprise photo — Lauren Yates)

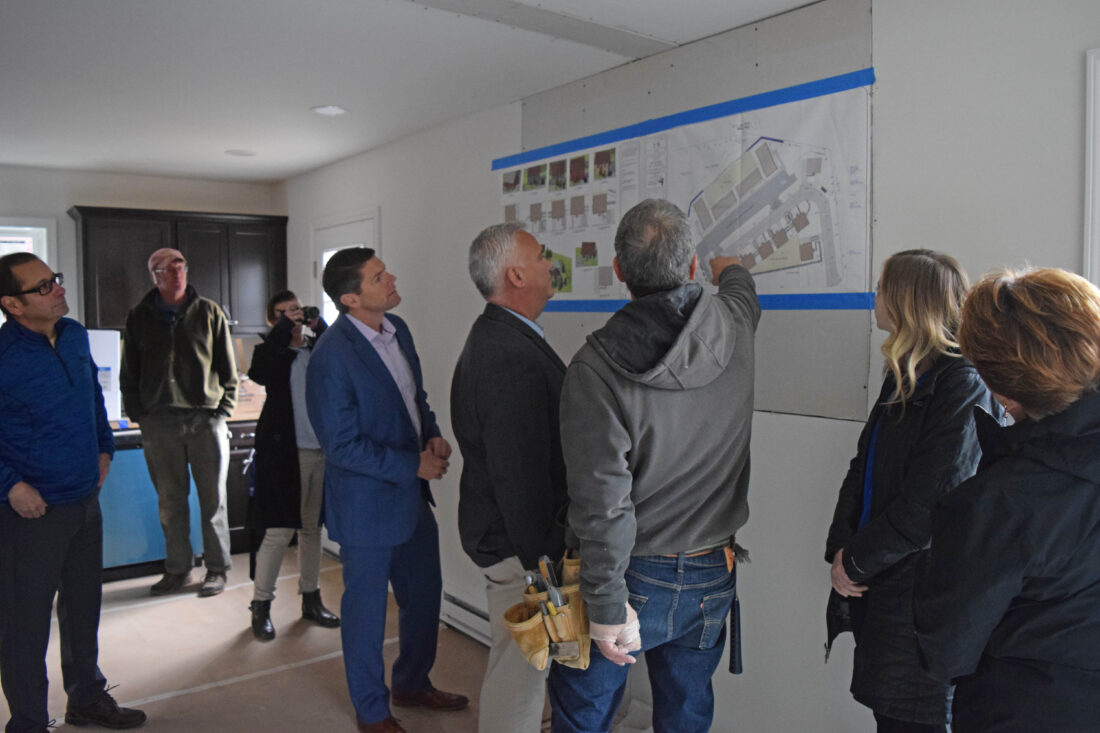

- Homestead Development Corporation President Steve Sama (center right) shows Assemblymen Matt Simpson (center), R-Horicon, and Billy Jones (center left), D-Chateaugay Lakes, the layout of the Fawn Valley housing development in Lake Placid on Monday, Oct. 17. (Enterprise photo — Lauren Yates)

At right, state Assemblyman Matt Simpson, R-Horicon, talks about the Fawn Valley housing development with Pat Fricchione, CEO and general partner at Simplex Homes, at the development on Monday, Oct. 17. Simplex is supplying the modular homes and townhomes for Fawn Valley. Assemblyman Billy Jones, D-Chateaugay Lakes, is seen center. (Enterprise photo — Lauren Yates)

LAKE PLACID — State Assemblymen Billy Jones and Matt Simpson want the state to allocate more money to fund housing projects aimed at middle-income homebuyers, and they believe a local housing development could help them make their case with lawmakers. The Assemblymen made their case locally during their visit to Fawn Valley on Wesvalley Road Monday, Oct. 17.

Fawn Valley, spearheaded by local nonprofit Homestead Development Corporation, isn’t like most housing developments that are in the works around the region. In the state’s eyes, it’s not an “affordable housing” project — a development with home prices or rent ranges aimed at people who make 80% of the area median income or lower. And it’s not a long-term rental project or a hotel resort development aimed at tourists. It’s somewhere in between.

It’s a six-home, 16-townhome development that’s aimed at local, essential workers who make around 200% of the AMI, which HDC President Steve said is around $147,000. North Elba’s AMI was $63,031 as of 2020, according to an Essex County demographic and housing report released in May.

Fawn Valley provides what Sama calls “reasonable” housing. But because the housing development isn’t considered affordable by the state’s standards, it doesn’t qualify for state-funded housing development grants, which are usually intended for low-income housing projects. But Sama says lower-income people aren’t the only ones who need housing that’s affordable to them now. He said middle-income workers are also being “priced out” of the local housing market.

Jones, D-Chateaugay Lake — whose 115th District is being redrawn in January to include five Essex County towns, including North Elba — said the top issue on constituents’ minds in the area is the need for more housing that’s affordable to people with middle-range incomes. Essentially, he said, the need for affordable housing isn’t only an issue affecting people who make around 80% of the area’s median income or below — it’s also affecting middle-income people. Jones declined to specify the AMI range he considers to be “middle-income,” but he believes projects like Fawn Valley are serving those people.

Homestead Development Corporation President Steve Sama (center right) shows Assemblymen Matt Simpson (center), R-Horicon, and Billy Jones (center left), D-Chateaugay Lakes, the layout of the Fawn Valley housing development in Lake Placid on Monday, Oct. 17. (Enterprise photo — Lauren Yates)

HDC board members said that Fawn Valley has been a community effort. HDC was able to create a 501(c)(3) for the project, and Sama said HDC is financially “cobbling together the dough” for the development with a combination of grants, lines of credit, private donations and private loans to make the project happen.

“It shouldn’t have to be like that,” said North Elba town Councilor Emily Kilburn Politi, who represents the town on HDC’s board. “A government should be able to recognize that you’ve got to raise that threshold.”

–

Convincing the colleagues

–

Jones and Simpson, R-Horicon, said they visited Fawn Valley last week to learn more about how they can help expand state funding opportunities for housing developments aimed at higher AMI levels. Simpson currently represents the town of North Elba in the 114th Assembly District, until Jan. 1 when the district’s new lines take effect. He and Jones said they saw Fawn Valley as a model for other potential middle-income housing developments, but Jones said that, at the state lawmaker level, it’s been hard to convince his colleagues that people with multiple income ranges are struggling to afford housing.

Fawn Valley caps income eligibility for homeowners at 200% of the AMI, which Sama believes is around $147,500. Referencing Assembly sessions, Jones implied that his colleagues tend to shy away from funding projects that serve middle-income homebuyers.

Simpson said he agreed with Jones’s points about expanding state-funded housing development opportunities for higher AMIs. He spoke from personal experience about the difficulty of finding housing he can afford in his Horicon community. Simpson said he’s coming to the end of a 15-year mortgage, and he thought about selling his home and buying a new one. But while his property value has “skyrocketed” over the last couple of years during the pandemic-related real estate boom — he said his property’s assessment value has more than doubled since the start of his mortgage — so have other property values in the area. With rising home prices and escalating interest rates, Simpson said, he was “priced right out” of buying a new home locally.

“We can’t afford to buy anything that’s available in Horicon,” he said.

Assemblymembers are in the midst of a multi-year raise that’s expected to culminate with a $130,000 annual salary — less than 200% of North Elba’s AMI.

“We have to try to do something — what can we do?” Jones asked Sama. “I think we have to convince our colleagues, executives — whoever — (that) there is a difference. … You have to have them buy into this concept, and that’s what our job is going to be,” he added.

–

Expanding the criteria

–

Sama said the state could help by providing more grants to these higher-AMI projects so developers can keep home costs affordable to people with those income levels. Several local officials said Fawn Valley wouldn’t be possible without the collaborative funding and developmental efforts between private donors, the Adirondack Foundation, Champlain National Bank, the Regional Office of Sustainable Tourism, the town of North Elba and others.

Sama said Fawn Valley will cost around $4.2 million to develop — the houses were around $1.6 million, and the townhomes were around $2.6 million. A private donor provided the land, which has an estimated land value of around $350,000. The HDC is selling the homes and townhomes at cost — around $220,000 for the homes and $180,000 for the townhomes — but Sama said that private grants and donations made that possible. All in all, Sama said, 25% in state funding would be an ideal funding supplement for a project like Fawn Valley.

ROOST Chief of Operations Mary Jane Lawrence, who was present during the Fawn Valley visit by Jones and Simpson, suggested that state lawmakers use the income criteria Fawn Valley uses — like the 200% AMI income cap — as the basis for criteria when expanding state-funded housing programs to include middle-income projects.

The development will also be deed restricted to ensure that the homes could never be used as short-term vacation rentals, and that they can’t be “flipped” for profit or rented. A homeowner could realize their equity on the home through a sale, but the homes are intended to remain “affordable” to people around the 200% AMI in perpetuity. The homes are set aside for people who provide essential services to the community, according to Sama. Eight of the townhomes have been set aside for staff at the Lake Placid Central School District and Adirondack Health.

–

“Ripple effect”

–

Sama said that the only way the HDC could get the OK to create a 501(c)(3) was on the proving grounds of “community deterioration.” While the IRS typically considers community deterioration applicants literally, according to Kilburn Politi — with past applicants showing proof of buildings falling down around their communities — the HDC was able to earn the exemption by proving that community deterioration also manifests as a vanishing workforce and declining school enrollment.

“We just proved it on a philosophical point,” Kilburn Politi said. She felt like HDC “cheated the system.”

The lack of housing for varied incomes has a “ripple effect,” Sama said. Without places for people to live, local schools, emergency services and health care facilities — along with local tourist and retail businesses — are having a hard time recruiting and retaining staff.

“If I had a dime for every help wanted sign I’ve seen (here), I’d be able to afford a house here,” Jones said. He stressed the need to both attract and retain residents to maintain the local workforce.

The setting of Jones’ and Simpson’s talk with local officials last week was Kari Hoffman’s future living room at Fawn Valley. Her home was the first to arrive at the construction site in August. Hoffman is a mother who works in the tourism industry. Her family has lived in Lake Placid for generations, and Fawn Valley is more than just a home to her. Kilburn Politi said Hoffman’s application for the home proved that she believes in the importance of Fawn Valley’s mission to house local workers.

“Being able to own a home in the place you’ve grown up in is a big deal,” Hoffman said.