Taking care

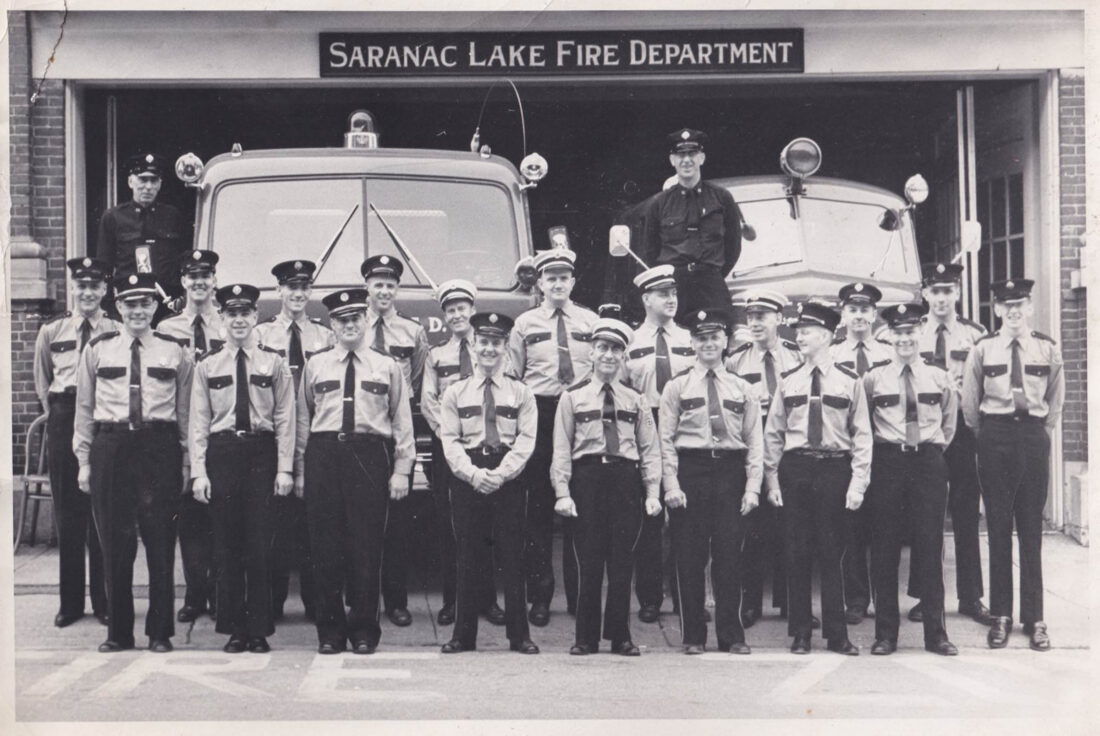

- Saranac Lake Volunteer Fire Department (Photo provided — Historic Saranac Lake Collection, 2022.17.8.139. Gift of the Duquette/Rice Family.)

- Nurses at the Trudeau Sanatorium. (Photo provided — Historic Saranac Lake Collection)

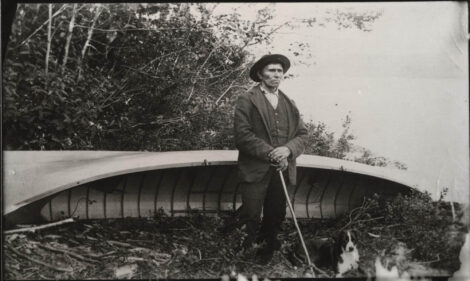

- Mitchell Sabattis, Long Lake, September 1886. (Photo courtesy of the Adirondack Experience.)

Saranac Lake Volunteer Fire Department (Photo provided — Historic Saranac Lake Collection, 2022.17.8.139. Gift of the Duquette/Rice Family.)

Here in the Adirondacks, people tend to fall into two categories. There are the helpers and the people who need help.

As transplants to Saranac Lake 25 years ago, my husband and I usually fall into the second category, and that was especially true this past March. It was a needy month. First, one night as the temperatures dipped into the single digits, our old boiler broke down. A few days later, my mother visiting from Virginia took a bad fall. We weren’t in any way prepared for either event. We needed help, and it came the Adirondack way.

In our cold winters, minor accidents and breakdowns can quickly become disasters. Our remote location means supplies can be hard to come by. Crises are always just around the corner. A set of people have adapted to these harsh conditions to be incredibly resilient, capable, and community-minded. The helpers — the people who fix things and rescue people — tend to know each other. In many cases they are related, as often the helping professions run from one generation to the next. They are the masters of triage. They shift priorities to solve the most pressing problems first, and they call on each other in a pinch.

Caretaking has a long history in the Adirondacks, going back to the first Adirondack guides like Abenaki guide Mitchell Sabattis. His ancestors made their home here for thousands of years, adapting to the harsh environment and learning how to respect and utilize the natural resources. The first white settlers were not prepared for the long, harsh winters, and they relied on Native peoples’ wisdom and knowledge to survive.

Soon, wealthy people were coming to the region for sport and recreation. They depended on guides for their comfort and safety. Many guides found work at hotels or great camps, where they also served as caretakers, maintaining buildings, securing supplies, and guaranteeing a restful experience for seasonal residents. The profession continues today at Adirondack great camps. Many of today’s caretakers are carrying on skills they learned from their fathers and grandfathers.

Nurses at the Trudeau Sanatorium. (Photo provided — Historic Saranac Lake Collection)

As the tuberculosis industry flourished in Saranac Lake, some caretakers found work in large sanatoria. As opposed to seasonal camp work, the TB industry provided steady, year-round employment. Sanatoria caretakers maintained buildings and managed the provision of fresh food, clean laundry and medicine.

At the sanatoria, a new economy grew based on another kind of caretaking — providing medical care. Countless doctors and nurses attended to thousands of people from around the world. Anecdotally, we understand that the medical professionals in Saranac Lake tended to have a special sympathy for their patients, as almost all of them were tuberculosis patients themselves. The TB industry closed in the 1950s with the advent of antibiotic treatment, but many Saranac Lakers are descendants of those medical professionals. Some have followed in their ancestors shoes, studying to be nurses and radiologists at NCCC, and serving as staff at our local hospital.

This March, we benefitted from Saranac Lake’s caretaking tradition. When our boiler shut down, we called Mike Boon and Lynn Martin. Seven years ago, they nursed our old house out of foreclosure and back into life. The day the heat went out, Mike and Lynn were on the scene in minutes to get the boiler working again and to arrange for a new heating system.

That week, as Mike and Lynn made their way home after working on our boiler, my mother fell. They heard the ambulance call come in across the scanner, because, of course, Mike doesn’t just fix things, he also puts out fires as a volunteer firefighter. Mike and Lynn knew help was on the way, and within minutes, the rescue squad had arrived.

Calling 911 is a moment of total vulnerability. When the helpers arrive, it’s a time of pure gratitude, that there are people in the world ready and willing to help a stranger. From the trip to the ER in the ambulance to three days at Adirondack Health, we met scores of helpers, hardworking and kind. My mom is back home with us and on the mend. She’s enjoying spending time on our cure porch in Dr. Merkel’s old cure chair. It’s my turn to be a caretaker, and it’s an honor, for a brief time, to be a part of the club.

Mitchell Sabattis, Long Lake, September 1886. (Photo courtesy of the Adirondack Experience.)