The art of wilderness navigation

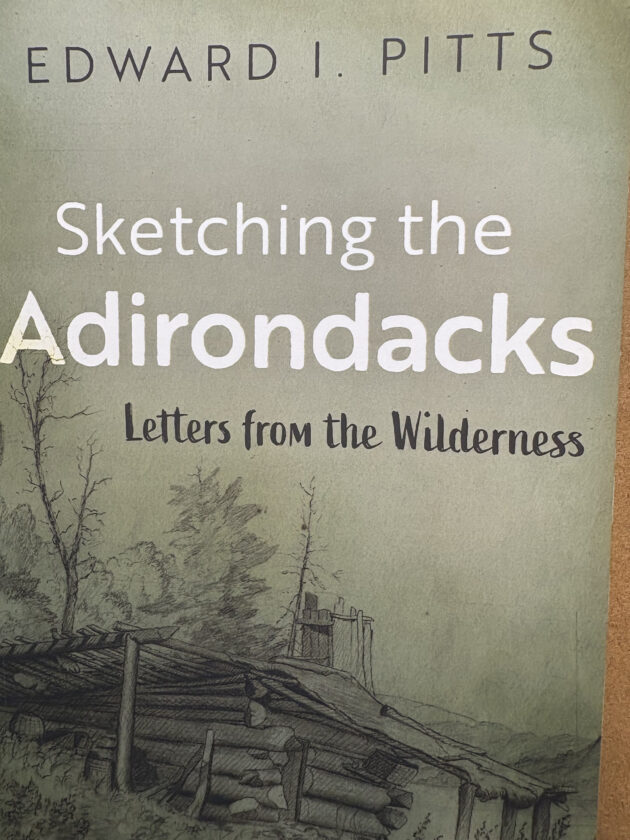

Review: “Sketching the Adirondacks Letters from the Wilderness,” by Edward I. Pitts

Imagine it’s 1851. You and a companion, both aspiring landscape artists captivated by the Romantic principles of the Hudson River School of painting, are trekking across the central Adirondacks, west to east, in search of inspiration and subject material. It’s a nearly trackless, almost uninhabited wilderness. And it’s a very rainy summer.

This is no fantasy. In that year, Jervis McEntee and Joseph Tubby, both in their twenties and both from the Hudson Valley, undertook exactly the journey/ordeal described above. What’s more, although neither of the young gentlemen could have been considered an accomplished outdoorsman, they both lived to tell about it. They were among the first, if not THE first, to transit the forbidding region for reasons other than resource extraction, and to purposely “rough it” in the decades ahead, more and more would come for those same reasons.

Their story is told in a unique new book, “Sketching the Adirondacks: Letters from the Wilderness,” by Edward I. Pitts, a retired attorney from Syracuse (Syracuse University Press, 2025). What’s unique is that Pitts, a skillful wordsmith, presents their expedition not as a traditional narrative restating McEntee’s journals, but as a series of fictionalized letters, all but one by Jervis, to family, friends, colleagues. Supported by Pitts’s deep dives into those journals and accompanied by his explanatory essays sprang from thorough research into the journals’ contexts, they enliven the adventurous duo’s experiences far better than a simple “they went here, then they went there” recital.

In the publishing world, it’s a given that fictionalizing historical facts and then alternating them with interpretive non-fiction is risky business. It’s bound to fail, most publishers will say, especially after attempts to craft the fiction in the style, language, grammar, syntax of 175 years ago. But Pitts pulls it off, both writing the fictional letters convincingly — “Your obedient son,” Jervis signs off on a letter to his parents — and blending fact and fiction smoothly enough that they do not grate but complement each other. Maps and high-quality reproductions of several of the pair’s sketches further augment the text.

The trip spanned two months and 170 daunting miles by foot, rowboat and lumber wagon from Boonville on the Black River to present-day North Hudson on the Schroon. They made their way up the Beaver River and on to Raquette Lake, Long Lake, Indian Pass, Mount Marcy (which they climbed) and out to civilization. They met characters like Asa Puffin, their prodigiously powerful and generally agreeable guide; Mitchell Sabattis, legendary indigenous inhabitant of the interior; the famed guide John Cheney; and the occasional hermit, who regarded them with varying levels of hospitality. They fought clouds of black flies. They left some of their gear behind and had to backtrack to retrieve it. Their boots fell apart. They got soaked over and over. And yet they remained cheerful and optimistic.

McEntee and Tubby, although they never gained the fame of artists such as Thomas Cole, Sanford Robinson Gifford or A.F. Tait, went on to modestly successful careers as landscape painters whlle engaging in other income-producing activities. They remained friends for the rest of their lives.

Today, travel through the Adirondacks is easy, summer traffic notwithstanding. This entertaining and instructive volume will convince any reader that it wasn’t always so.