Misadventures with Pancho

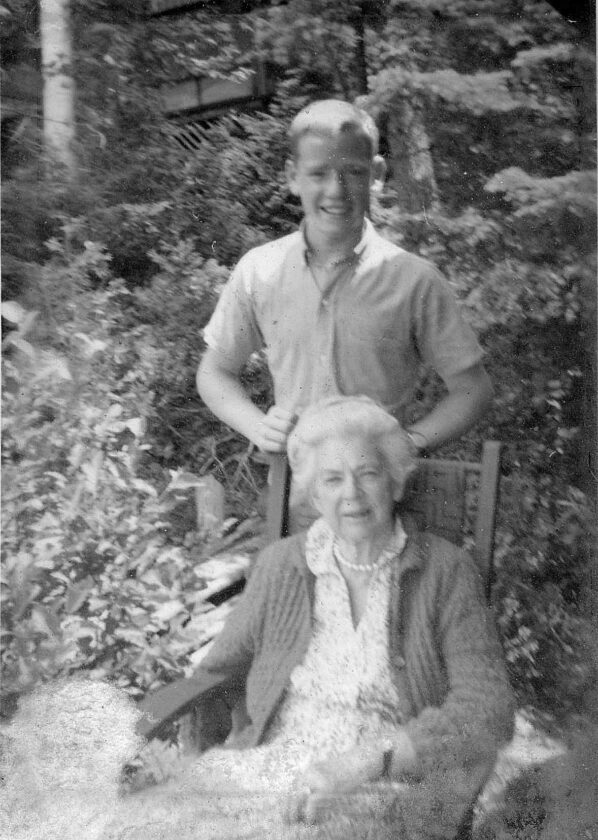

Jack Drury, alongside his great aunt Marnie, around 1961. (Provided photo — Jack Drury)

In the early part of the 20th century, every red-blooded American knew who Pancho Villa was. Many thought of him as a brutal villain, yet to just as many, he was the poor man’s hero. He was known to be an excellent leader and a great battle strategist. While Pancho Villa was in Mexico fighting the ruling class, causing havoc, Saranac Lake was fighting tuberculosis, with patients lying on cure chairs on outdoor porches year-round. Most amazingly, while most of these things took place thousands of miles apart, there was a connection between the two.

Like so many Saranac Lakers, my family and I were drawn here by tuberculosis. No, I never had TB, but my namesake great uncle Jack Kane did. And although he died before I was born, as a kid, I heard of some of his adventures from his wife, Marjorie Simmons Kane (Aunt Marnie to me). Uncle Jack started visiting the Adirondacks in 1901 and visited off and on until 1920, when he purchased the Mark Twain Camp. He died in Saranac Lake in 1936 at the age of 49 … of TB. Those facts are established, but what we don’t know is how he got TB.

Jack Kane was the great-great-grandson of John Jacob Astor, who was America’s first multi-millionaire.

They say that family fortunes don’t last more than three generations, which must be the case because I never saw one. Don’t get me wrong, my family was upper middle class with its share of privilege, but millionaires?

Not even close.

So how did my great uncle Jack end up with TB, and what does any of this have to do with Pancho Villa? Read on.

In 1906, Uncle Jack went to work for the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), one of the titans of the mining and refining industry. By 1912, he, along with his brother-in-law and my grandfather, were mining engineers in El Paso, Texas. They spent much of their time in Mexico managing the mines and smelters. My dad grew up in El Paso and went to work for ARSARCO many years later.

I can only imagine what life was like working for an American mining company in Mexico during that time. Between 1910 and the early 1920s, Mexico was the scene of continuous revolt and rampant banditry.

During the Mexican Revolution, there were an estimated 1 to 2 million deaths. Revolutionaries not only included Pancho Villa but Pascual Orozco, and Emiliano Zapata as well. They were the triumvirate of warlords of that time. They all opposed dictator Porfirio Daz, who seized power in a military coup and served as President of Mexico for over 30 years.

ASARCO’s relationship with Villa was complicated. The mines and refineries were in territory controlled by Villa. His opinion of the company was made clear when he stated that the only English he knew was, “Si, American Smelting and Refining Company is son-of-bitch.” On the other hand, he knew that ASARCO was a good employer providing good jobs. He went back and forth in a schizophrenic frenzy between guaranteeing ASARCO’s American employees’ safety and attacking the trains they traveled on.

As a child, my Aunt Marnie regaled me with tales of traveling through Mexico by train. The train was stopped by Pancho Villa and his men numerous times. She would hide her jewelry in her hair so it wouldn’t be stolen. She also, at least once, had to hide important company papers from Villa’s men.

In adulthood, I learned of the most famous train incident of the era. Known as the Santa Isabel massacre, it took place on January 10, 1916, at Santa Isabel, Chihuahua, Mexico. Mexicans led by one of Villa’s most loyal lieutenants stopped a train and removed 17 American citizens who were employees of ASARCO. All but one of the Americans were summarily robbed, stripped and executed. I never learned what my great uncle or Aunt Marnie knew about it, but it couldn’t have done much for ASARCO and Pancho Villa’s relations.

Another of Aunt Marnie’s tales was when Great Uncle Jack and some colleagues and their families were caught in a mountain village surrounded by Pancho Villa and his men. According to her, late at night, Uncle Jack and his colleagues put the women and children in a boxcar and pushed it down the tracks until, under its own momentum, it took the women and children to safety. For his bravery, he got a medal from the U.S. Secretary of State.

It wasn’t until a few years ago that I learned of the ultimate connection between my Uncle Jack and Pancho Villa. It came from my dad’s sister. She was 92 when during my visit she said, “You know, I think Uncle Jack got TB when he was captured by Pancho Villa.”

“What? I never heard that story.” “Yes,” she said, “Not only was he captured by Pancho Villa, but he was held prisoner for two months in a cave.”

“In a cave?”

“Yes, I think he got TB from being stuck in that cave and having to cook over an open fire.”

I regret that I never got to quiz my grandfather or Uncle Jack about their adventures with Pancho Villa.

Villa was gunned down near where they worked in Parrel, Mexico, on July 20, 1923. His last words supposedly were, “Don’t let it end like this. Tell them I said something.”

It’s too bad he was a revolutionary and not a newspaper columnist. If so, his last words would have been much more profound. And if not more profound, at least more entertaining.