Wilderness Management: A contradiction in terms?

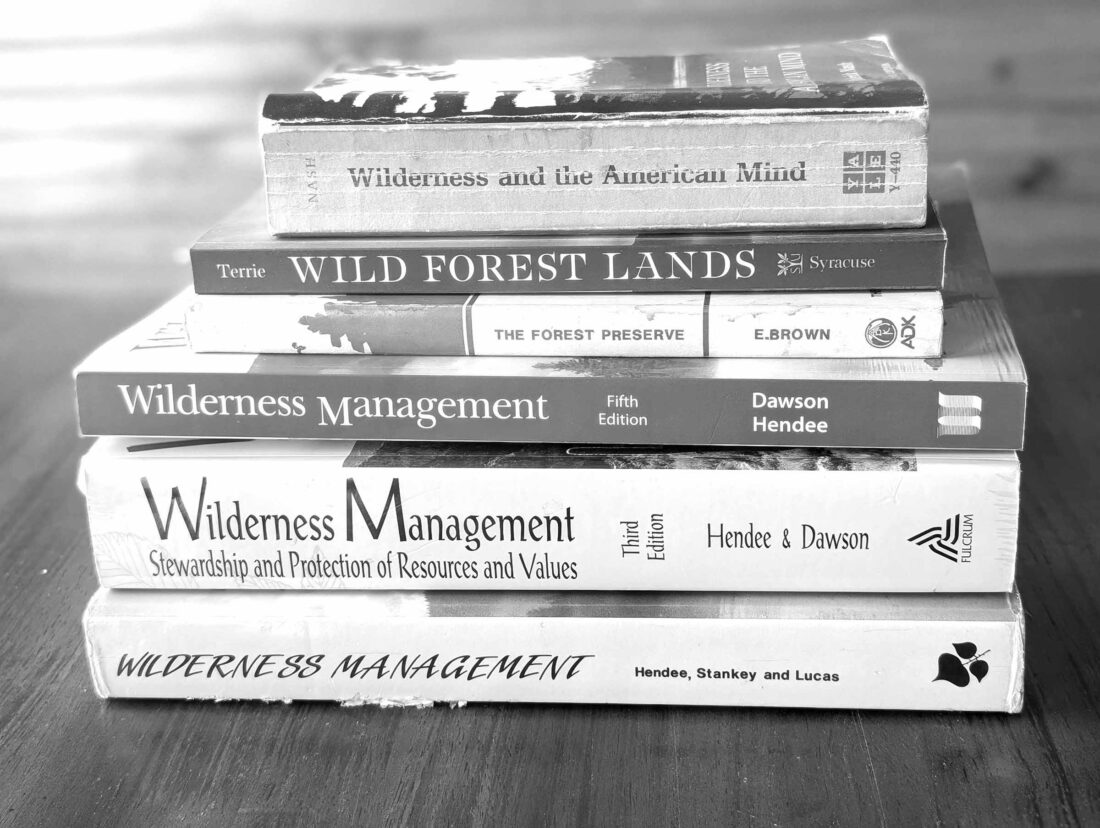

Some fine references for the serious Wilderness enthusiast. (Provided photo — Jack Drury)

I feel sorry for those who don’t enjoy reading, for they’re missing out on humanity’s greatest invention … the book.

The joy of reading is something my mother instilled in me at an early age. I remember going to the Locust Valley Public Library before I could read. My mother would pick out books for me, and we’d bring them home, where she’d read them to me and I would study the pictures. Dr. Suess was a favorite. When I was 12 my family moved to the Finger Lakes and I fell in love with historical fiction. The “We Were There” series, written in the mid-1950s through early 1960s, told the story of major historical events through the eyes of child protagonists. I devoured them.

My high school reading selections migrated to sports, both biographies of the greats and sports fiction. My college years started my love affair with outdoor books, and I think I have a world-class collection of them, many autographed by the author.

When asked what my favorite outdoor books are, my response is always the same: What are your criteria? When in Japan a couple of years ago, I was asked the question by a group of Wilderness Educators. I didn’t hesitate in saying, “I’m a bit prejudiced, but if you want to be the best teacher of wilderness leadership, you may want my text, “The Backcountry Classroom.” And if you want to understand the uniqueness and meaning of Wilderness, you need Roderick Nash’s “Wilderness and the American Mind.” I felt pretty good when a gentleman came up to me afterward and said those two were the only books he kept from his undergraduate years.

For Wilderness managers and serious Wilderness enthusiasts, I’d add another: “Wilderness Management.” The first edition, published in 1978, was authored by John C. Hendee, George H. Stankey and Robert C. Lucas, pioneers in the field of wildland management. It was the seminal text in the field, and I used it and its second edition as the primary text in my Wilderness Management class for my entire career. The latest edition is edited and updated by Chad Dawson. It isn’t light reading, but the book’s thirteen principles provide the perfect lens for Wilderness managers as they make their myriad decisions. I can’t cover all thirteen here, but let me share how a couple have impacted my thinking.

Principle 1: Manage Wilderness as the most pristine end of the environmental modification spectrum. That’s a mouthful–so what does it mean? Over the years, I’ve been accused of not being “green” enough on some public land issues, while at the same time being too rigid when it comes to Wilderness. This principle helps explain why.

It recognizes that landscapes exist along a broad spectrum, from paved urban streets to suburbs with pocket parks. From working rural lands to roadless wildlands. And finally, to the most remote and untouched places on Earth. Wilderness sits at the far, natural extreme of that spectrum. Here, human influence is minimal and the defining qualities — naturalness and solitude — matter most.

Seeing Wilderness this way has clarified something important for me: Not every wild place needs to be designated as Wilderness. But if it is designated, then it damn well oughta be managed that way — no compromises.

Principle 3: Manage Wilderness and sites within, following a concept of nondegradation. This principle acknowledges that not all Wilderness areas are equally wild. The goal is simple but demanding: A designated Wilderness should never become less wild, and over time, it should become wilder.

On a national scale, that might mean recognizing that many Eastern Wilderness areas don’t match the raw wildness of Alaska’s. But the challenge isn’t to lower their bar–it’s to make sure none of them lose what wildness they have, while steadily pushing the Eastern ones closer to the ideal.

Dawson’s newest edition of “Wilderness Management” continues the legacy of the original authors while updating the content, particularly as it applies to the concept of carrying capacity and visitor management. What is carrying capacity? The concept goes back to the 1800s and the creation of livestock ranches. It focused on how much land was needed to support cattle. Obviously, it depended on things like the ground cover, the availability of water and how many months a year the cattle grazed. Carrying capacity, as it relates to wildlands, focuses on how many people can use an area before it loses the qualities we want in an outdoor recreation experience.

Since the days I taught Wilderness Management, the concept of determining carrying capacity has evolved considerably. The current iteration is called Visitor Use Management or VUM. It is the practice of guiding when, where and how people use wilderness, so visitors’ experiences are protected while the area’s natural conditions remain unimpaired. Wilderness managers focus primarily on visitor management because it is vulnerable to the cumulative effects of people, including well-intentioned ones. Managing use is how managers protect both the land and the experience that makes wilderness wilderness. The DEC and its consultants are currently exploring how the Visitor Use Management Framework process might look if applied to the High Peaks Wilderness Complex. I’m anxious to see what they come up with.

I’m grateful to Chad Dawson for carrying the torch on the fifth edition of “Wilderness Management.” It’s a great book, but like any text, it has its weaknesses. In this case, and it exists in all editions, is that it’s so abstract. The challenge is to take these largely academic concepts and help managers understand and be able to apply them. In addition, it is essential for the public to understand and have ownership within the process. We need to go beyond case studies and give learners collaborative exercises where they can practice applying these concepts.

Lest you think there is already too much Wilderness, let me share why I think we have a long way to go before we need to worry about having too much. When we have as much Wilderness in the lower 48 states as we do pavement, when we have as many wild mammals and birds as we do domestic … then we might have enough wildness in the world.