Should I take a left or right?

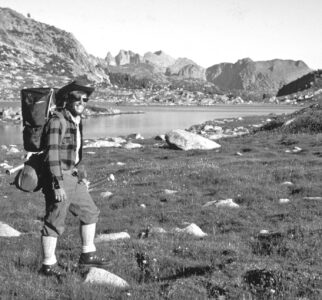

- Jack on his first NOLS course. (Provided photo — Jack Drury)

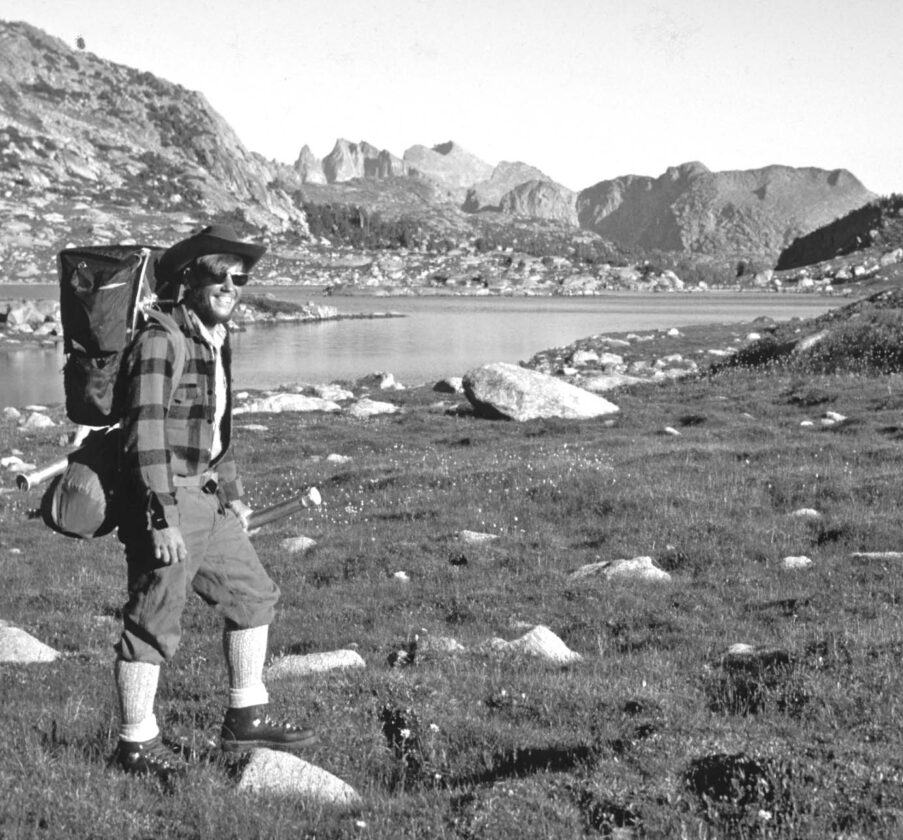

- Jack Drury, far right, with his “survival” group. (Provided photo — Jack Drury)

Jack on his first NOLS course. (Provided photo — Jack Drury)

Have you ever pondered how you ended up on the path that you took? Robert Frost in his classic poem, “The Road Not Taken,” highlights the idea that choices, no matter how big or small, shape our lives. I think it was author Jack London who talked about walking down the street in San Francisco and taking a left instead of a right and for that, his life changed forever. Don’t we all have our own version of that?

If my dad hadn’t died my senior year in high school, I would have never studied recreation at the University of Wyoming. (He wanted me to go to Princeton and study business.) If I hadn’t gone to the University of Wyoming, I would have never met mountaineer and wilderness educator Paul Petzoldt. If I hadn’t met Paul Petzoldt, I would have never gone to the National Outdoor Leadership School. If I hadn’t gone to NOLS, I would never have met my friend Dave Iuppa. If I hadn’t met Dave Iuppa, I would have never climbed Denali. If I hadn’t climbed Denali … You get the idea.

There were too many decisions in my life to count, both big and small, that brought me to this point. There was also a lot of serendipity. My life, like all our lives, has been a combination of both.

But it started with my decision to attend the University of Wyoming. My sophomore year was the first time I saw Paul Petzoldt. It was at the Washakie Cafeteria where Al Hendricks pointed him out to me.

“That’s Paul Petzoldt, he’s a famous mountaineer.”

Jack Drury, far right, with his “survival” group. (Provided photo — Jack Drury)

I couldn’t understand why the man who climbed the Grand Teton in cowboy boots at the tender age of 16, did a double traverse of the Matterhorn in a single day and almost summited K-2 in 1938 — arguably the most difficult mountain in the world to climb — helped start the first American Outward Bound School, and NOLS was doing eating at our cafeteria. He was 60 years old.

He was barrel-chested, six feet tall with white hair and big bushy eyebrows. It turns out that since starting NOLS three years earlier, he had been traveling the country giving presentations about his new school. He decided to take a course in public speaking and live on campus to improve his speaking skills and get an understanding of why students were rioting across the nation during this period of unrest. The conservative University of Wyoming was probably not the best place to get that understanding.

A few months later, he gave a presentation about NOLS, and it set me on my life’s course. To say I thrived on my NOLS course is an understatement.

My first indication that I wasn’t in Kansas anymore was when our patrol of 10 students humped our heavy packs all day. As the sun started setting, I heard a murmuring, “I don’t think the instructors know where we are.” It turned out the kid was right. We were lost.

But then it hit me: It didn’t matter. We had 10 days’ worth of food and everything we needed to live comfortably. We weren’t going to be lost for 10 days. As my friend Peter Kelley likes to say, “What’s the worst that could happen?”

Sure enough, within a couple of hours, not only did our instructors figure out where we were, but they brought us into camp where our fellow students welcomed us with a hot meal of mac and cheese a la brook trout.

On that first course, I not only learned that it was okay to not know where you were, but I learned to navigate, to cook nourishing and delicious meals over a fire, to rock climb and, most of all, I learned to be comfortable in uncomfortable situations, I also gained some valuable leadership experience.

In those days, each patrol of 10 or 12 students broke into small groups of four to six and went on a five day “survival” trip with no food. I didn’t know any of my fellow students, as they were from another patrol. Our instructor, John Cress, prepared us by saying, “We only have one set of maps for the survival groups and the instructors. The instructors are going to keep the maps, but you can make sketches from them. Drury, you’re going to be leader of the first group. Roy, Chris and Tom, you’re in Drury’s group.”

He added, “There are some rules we want you to follow. First, you have five days to get to the trailhead. We don’t want you to arrive early. Take your time, enjoy the five days and plan to arrive the morning of Aug. 31st. Second, in an emergency, go out to the Hidden Valley Ranch or out the Cold Spring Jeep Trail. Third, this is a final exam of sorts to see how you use your resources and skills to safely travel through the wilderness. You’ve learned about expedition behavior and to respect others that you encounter. You’ll be traveling on Indian Reservation land, and the trailhead is on private ranch property. Avoid interacting with people, but if you do, treat them with respect. No bumming or begging for food in any way. Have a great trip, and we’ll see you in five days.”

That evening, I studied the maps exhaustively and made sketches of the terrain in my notebook. We headed out the next morning brimming with confidence, but only some powdered beef broth for food. We were hopeful that we would find our way and wouldn’t starve.

The first two days were great. The fish were biting and the huckleberries were ripe. We caught 12 fish and pints of huckleberries. We were living high on the hog. Unfortunately, the last three days we caught only one fish and found no more huckleberries.

Unbeknownst to us, there had been a forest fire on the Indian reservation lands. Firefighters were just wrapping up their work. Tired and extraordinarily hungry, we trudged through ankle-deep ashes towards our rendezvous point. We started seeing signs of the firefighters, things like empty fruit cocktail and peach cans. They were a terrible tease, but not as bad as what we encountered next. As we worked our way down the ash-filled trail, I was in the lead and suddenly saw a plastic bag with three sandwiches in it.

I looked at the bag, and there they were: three fresh sandwiches. They were speaking to me and my growling stomach. It was just me standing ankle deep in ashes with the three sandwiches. Here’s what they said to me. “We’re delicious. You’ve had nothing but a lousy fish for the last three days, eat us!” I had to make an immediate decision before the others caught up to me. Although I was never a Boy Scout, I might as well have been. For most of my life I’ve been a Mr. Goody Two shoes. So, no, it never crossed my mind not to tell the others about the sandwiches. Instead, it was about whether we should eat them or not.

I instantly had to make one of the biggest decisions of my life. Do we eat the sandwiches? According to the rules, we were not “bumming or begging for food in any way”… But, while I felt that the letter of the law allowed us to eat them, I felt the spirit of the law said no, we shouldn’t. I also knew that trying to sell that to my fellow wilderness travelers would be like nailing Jello to a tree. I didn’t give them an opportunity to be part of the decision. With them watching, I threw the sandwiches in the bushes and kept walking.

That night Chris said, “I think you made the wrong decision. We should have eaten them.” Maybe he was right.

I learned that big decisions were easy to second guess. It may have been the first big decision I made outdoors, but it certainly wasn’t my last.