A gift for Henry James

Headline: “Dr. Kinghorn Receives Stevenson Picture,” By Bob Waters, Special to the Watertown Daily Times.

“Saranac Lake, March 5, 1948, — Dr. Hugh Kinghorn, president of the Stevenson Society of America, has received another relic of the famous author to add to the already impressive array of Stevenson souvenirs on display at Baker Cottage, Saranac Lake’s famous shrine to the memory of the author.

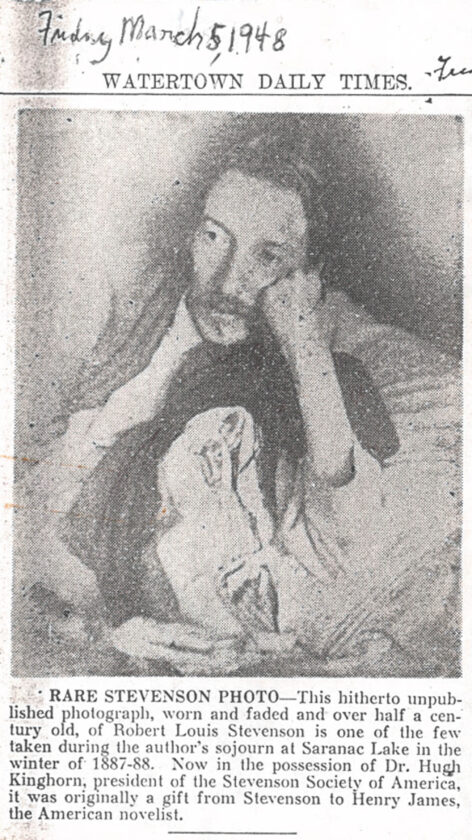

“The relic, an autographed photograph of Stevenson, was taken while he was spending six and a half months in the Adirondacks. It was originally presented by Stevenson to Henry James, the renowned writer. Framed in gilted porcelain, the picture passed from James to Austin Strong, son of Stevenson’s stepdaughter, and from Strong to Dr. Kinghorn and the society.

“The photograph, one of only two taken during the suthor’s sojurn at Saranac Lake, carries Stevenson’s autograph and the word, ‘Eheu.’ Latin for ‘alas,’ believed to refer to an ode of Horace, the first line of which is ‘eheu fugaces labuntur anni,’ which translates, ‘alas, the fleeting years glide by.'”

Robert Louis Stevenson and Henry James were best friends, which usually comes as a surprise to people who know enough about both of them to even have an opinion. Whatever their perceived differences might have been, they had one thing in common — a healthy respect and love for their craft. Both men aproached their art with greater seriousness and intensity than their contemporaries like Hardy, Meredith, Barrie and Kipling, to name a few. They were also exasperated by the indifference of their peers toward their artistic ideals and goals. This exclusion made them soulmates.

Henry James was an American expatriate living in France when he became pen pals with Robert Louis Stevenson, living in England. They had discovered a cerebral kinship through articles they had placed in Longman’s Magazine. In 1885, James moved to Bournemouth, England, to help an ailing relative. That’s where RLS was living with his wife, Fanny, and stepson Lloyd Osbourne. The pen pals finally got to meet face to face.

Henry James became a regular at “Skerryvore” the name of Stevenson’s yellow brick house with a blue slate roof and a cliff at the end of the back yard with a view of the English Channel. He was probably the most frequent and most welcome among the guests at Skerryvore. A large deep blue arm chair was so well used by him that it was christened “Henry James Chair.” As a relative newcomer in Stevenson’s circle, James had managed to avoid the collision of interests that came into play when his friend married an older American woman in 1880. Stevenson’s set would probably never have confessed to jealousy, it was just that their old friend was a better friend before she came along.

Mrs. Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne Stevenson got on famously with Henry James. He was a fellow American and he devoured with relish the native cuisine she cooked up for him and Fanny could cook. For a bachelor, James had an uncanny ability to write about kids. It brought Fanny to tears when she read about a fictional boy in “The Author of Beltraffio,” that reminded her of a boy of her own from her first marriage, who had died tragically young.

By the spring of 1887, the winds of change were blowing around. Thomas Stevenson, the author’s father, had died in May, in Edinburgh. RLS had been living in Bournemouth because people believed that its congenial climate made it the best place in Great Britain for invalids. But Louis was nagged by something a doctor had told his step-son, that the climate of the British Isles, even in Bournemouth, was a slow poison. And his American spouse was homesick.

A plan came together. With Thomas gone, there was nothing to keep him in Britain. Dr. George Balfour was an uncle of RLS. It was his idea that the whole group, including Margaret Stevenson, the recently widowed mother of Louis, book passage to the U.S. with a will to get to Colorado Springs.

With the wheels in motion, things went fast. Soon came the night when Henry James raised himself from his big blue chair at Skerryvore for the last time as the friends bid farewell. A few days later, just before she sailed from London, James had sent a case of champagne up the gangplank of the steamer S.S. Ludgate Hill to his voyager friends in case of “seasickness.” Then he sat down and wrote in his journal that “they are a romantic lot and I delight in them.”

There is ample documentation to prove that the Stevenson expedition never got to Colorado. The unpredictability of life as an invalid had again messed up the writer’s plans and the whole group — that being RLS and his wife, Fanny, his mother, Margaret, Fanny’s son Lloyd, and Valentine, their Swiss maid — all of them went for a detour into the heart of a mountain wilderness to a small frontier settlement with a strange new name — Saranac Lake — but usually they shortened that to “Saranac.”

Once settled into Baker’s for the winter, Louis wrote his first letter from Saranac to his friend in England: “My dear Henry James, This is to say that First, the voyage was a huge success … sixteen days at sea with a cargo of hay, matches, stallions, and monkeys (zoo animals were the main cargo) and a ship that rolled like God Almighty …” RLS wrote more than one letter to James from Saranac. On Nov. 20, Louis told him, “how are family has been employed. In the silence of the snow, the afternoon lamp has lighted an eager fireside group; my mother reading, Fanny, Lloyd and I devoted listeners; and the work was really one of the best works I ever read; and its author is to be praised and honored …” Roderick Hudson is the name of the novel and Henry James wrote it. “My dear Henry, it is very spirited and very noble, too … this letter is not from me to you; it is from a reader of R.H. to the author of the same, and has nothing to say but thank you.”

Nobody knows who took the photograph of RLS at Baker’s that became a newspaper story in 1948 but we do know who delivered it to its intendee, Henry James. That was Sam McClure, an American publisher who made several journeys from New York City to Saranac in the fall and winter of 1887-88. His intention had been to just talk business with the top star of the day but, like others, McClure would fall under the spell of this “spirit intense and rare” and when he started up his own McClure’s Magazine, he made sure to feature articles by Robert Louis Stevenson, this extraordinary man who could write, too.

When McClure made a business trip to England in March 1888, he took with him letters and gifts from RLS to deliver in person to various members of the latter’s set, including Henry James. Much to his surprise, he said he “found that most of Stevenson’s set was very much annoyed by the attention he was receiving in America, a most extraordinary spirit of hostility an jealousy. They were resentful of the fact that Stevenson was recognized more fully, more immediately and more understandingly in America than in England at the time … And personally, I was the very essence of what was most undesirable in Americanism — I was the limit — an American editor … they had all believed at that time that every American was ignorant — that Stevenson deserved great praise and high consideration for his efforts” but that his “London friends agreed that he was a much overrated man.”

McClure went on to say, “One man had just a heartful of love, friendliness and understanding of Stevenson and that was Henry James and there I had one of the most marvelous visits. He was Stevenson’s admirer. His interest in Stevenson’s health, his works, his plans for the future was wholly affectionate, wholly disinterested … Henry James was Stevenson’s friend and well-wisher. His loyal generous feeling I have never forgotten.”

“We are all travelers in the wilderness of this world; and the best that we find in our travels is a friend.” — RLS.

Robert Louis Stevenson and Henry James kept in touch. They had started out as pen pals and finished up that way with their last letters travelling half-way around the world. When news of Stevenson’s death reached Britain in 1894, it sent a shock wave through the whole nation but for his friends it was much worse. The effect Stevenson had made on his contemporaries can’t be overstated and Henry James spoke for them all in a letter to Sir Edmund Gosse, mutual friend, fellow writer and another future British Representative of the Stevenson Society in Saranac Lake:

“Of what can one think, or utter, or dream, save of this ghastly extinction of the beloved R.L.S.? It is too miserable for cold words — it’s an absolute desolation. It makes me cold and sick — and with the absolute, almost alarmed sense, of the visible material quenching of an indispensable light. That he’s silent forever will be a fact hard, for a long time, to live with. Today, at any rate, it’s a cruel, wringing emotion. One feels how one cared for him — what a place he took; and as if suddenly into that place there had descended a great avalanche of ice. I’m not sure that it’s not for him a great and happy fate; but for us the loss of charm, of suspense, of fun is unutterable.”

Today, after 135 years, the autographed photograph in the gilted porcelain frame, a gift for Henry James, is back after two trans-Atlantic trips, and can still be seen in the room where it was taken with the bed RLS was in, in the picture, still in the room.