The death of Stevenson

“It seemed unprovoked, a wilful convulsion of brute nature.”

— “Weir of Hermiston,” by Robert Louis Stevenson

With those words committed to paper, Robert Louis Stevenson, the famous invalid author from Scotland, quit writing for the day. It was late in the morning on Dec. 3, 1894. Weir of Hermiston is an unfinished novel set in Scotland. That quote up there is Stevenson’s last contribution to English literature. Ironically, the words seemed prophetic of the cerebral hemorrhage that killed him that very evening, a coincidence often noted in biographies.

The pen and pewter inkpot that Stevenson was using when he died has been sheltered at Baker’s, on Stevenson Lane, in Saranac Lake, since 1917. They are one of many gifts to the Stevenson Society of America from the author’s stepchildren, Lloyd Osbourne and his older sister, Mrs. Isobel Field, better known as Belle. Belle was Stevenson’s amanuensis (she took dictation), and to Belle, Louis dictated his last words of fiction. It was writer’s cramp, not illness, that made him turn to part time dictating. Being so close to the author, Belle was able to provide Sidney Colvin vital information for his editorial notes on the book, which all the experts agree was his finest writing to date, a masterpiece held in suspension by a burst blood vessel that popped “like a wilful convulsion of brute nature.”

It happened while he was at home. In 1894, home for the Stevensons was on the mountainous, tropical island of Upolu in the Samoan group in the South Seas. There the climate suited him best and there he settled in self-exile. The sudden wealth that had come to the author of Treasure Island when he was in Saranac Lake had enabled him to buy 380 acres on a plateau thick with jungle, 800 feet above the harbor town of Apia. A large clearing was cut and a big house was built in two sections and named Vailima by the new owner, a Samoan word signifying streams and waterfalls flowing through and over his property.

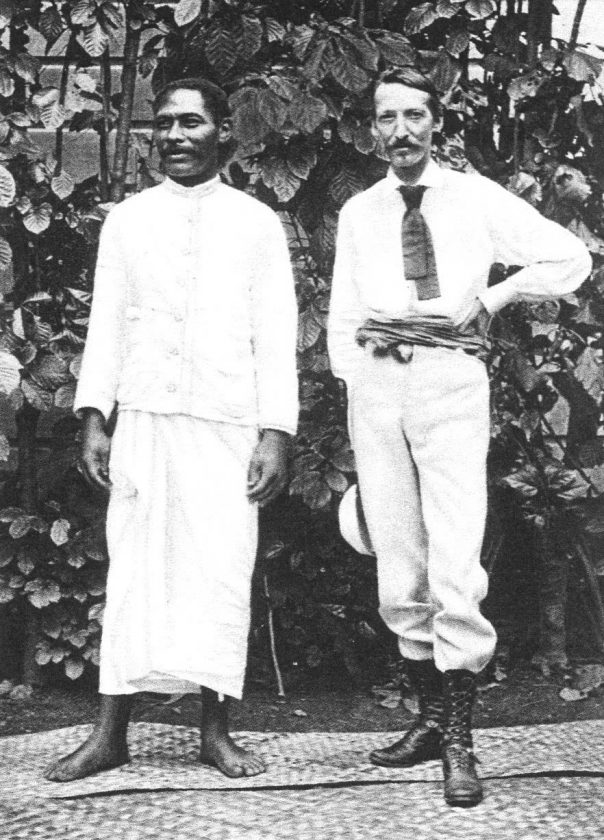

“Tusitala,” meaning “Teller of Tales,” was Robert Louis Stevenson’s Pacific specific name for this white man highly honored by the native people among whom he settled. His efforts on their behalf during a turbulent period was appreciated. They knew that this skinny white man had no self-serving motives and a number of them became functionaries in the Vailima household, feeling like family they would tell you.

Going from his second story study onto his veranda, with a view of the Pacific Ocean, must have given Louis some satisfaction, one might think. He had certainly accomplished more than he ever dreamed when he was an accomplished school-skipper; not just in terms of money but he was famous, too. They could see when a ship came in and when one did, they could expect any day to see carriages with tourists driving to the edge of his property, just to see it, maybe to see him, the author of Jekyll and Hyde. The bohemian of Fontainebleau who once gave away money like candy while ridiculing the bourgeois, had finally joined them but only in appearance, a Polynesian version of an English country gentleman with a large estate and multi-national household while caught up in island politics. And with it all came responsibility.

Lloyd Osbourne was there. He had been there most of the time, since his mother married Louis in May, 1880. Few people knew RLS as well as Lloyd. Many years later when he was president of the Stevenson Society of America, in Saranac Lake, Lloyd wrote a series of biographical articles for the Tusitala Edition of Stevenson’s works. In the last of these, “The Death of Stevenson,” he says: “Stevenson had never appeared so well as during the months preceding his death, and there was about him a strange serenity which it is hard to describe … I think he must have had some premonition of his end; at least, he spoke often of his past as though he were reviewing it, and with a curious detachment as though it no longer greatly concerned him … Several times he referred to his wish to be buried on the peak of Mount Vaea.”

Stevenson’s mother, Margaret or Aunt Maggie, was there, too, with her own spacious room and personal attendant. Just like she did in Saranac Lake, Margaret was still writing letters to her sister in Scotland, Jane W. Balfour. The hardest letter she ever had to write was the one from Dec. 4, 1894:

“How am I to tell you the terrible news that my beloved son was suddenly called home last evening. At six o’clock he was well, hungry for dinner and helping Fanny to make mayonnaise sauce, when suddenly he put both hands to his head and said ‘Oh, what a pain!’ and then added ‘Do I look strange?’ Fanny said no, not wishing to alarm him, and helped him into the hall, where she put him in the nearest easy-chair. She called for us to come, and I was there in a minute; but he was unconscious before I reached his side, and remained so for two hours, till at 10 minutes past 8 p.m. all was over.

“Lloyd went for help at once and got two doctors … but we had already done all that was possible … when it was all over his boys (domestic help) gathered about him and the chiefs from Tanugamanono arrived with five mats which they laid over the bed (two of these ceremonial mats are in the Saranac Lake collection); it was very touching when they came in bowing, and saying ‘Talofa, Tusitala’; and then after kissing him and saying ‘Tofa, Tusitala,’ they went out. After that our Roman Catholic boys asked if they might ‘make a church,’ and they chanted prayers and hymns for a long time, very sweetly … Louis wished to be buried on the top of Vaea Mountain, and before six this morning forty men arrived with axes to cut a path up and dig the grave.”

Lloyd Osbourne, stepson and sidekick of RLS, former president of the Stevenson Society of America and former resident of Saranac Lake, gets the last word:

“At two o’clock the coffin was brought out, and borne by a dozen powerful Samoans led the way up the mountain. Directly behind were thirty or forty more men who at intervals changed places with the bearers. It was a point of honour with them all to keep their heavy burden shoulder high, though how they contrived to do so on that precipitous path was a seeming impossibility. A party of a score or more white people followed interspersed with chiefs of high rank. Behind there again were perhaps two hundred Samoans in black ‘lavalavas.’

“The sun shone mercilessly; the heat was stifling. We were thankful that rain had not intervened. A heavy rain in Samoa is a veritable cloud-burst. We should never have been able to make the path had it rained, and the whole interment would have been robbed of its dignity and beauty. But the heat made it a terrible climb for some of our guests. There was one elderly white man who I thoughr would never reach the summit alive … ‘I am going on if it kills me,’ he said, deaf to all our entreaties to turn back. ‘I venerated Stevenson.’

“The photographs of Mount Vaea, like all photographs of mountains, diminish its height; it would be easy for one who has seen it only in pictures to get a very mistaken impression. From Vailima to the summit is a most formidable ascent for sedentary people, unaccustomed to exercise.

“We gathered about the grave, and no cathedral could have seemed nobler nor more hallowed than the grandeur of Nature that encompassed us. The sea in front, the primeval forest behind, crags, precipices, and distant cataracts gleaming in an untrodden wilderness. The words of the Church of England service movingly delivered, broke the silence in which we stood. The coffin was lowered, flowers were strewn on it, and then the hungry spades began to throw back the earth.”