‘My Good Health,’ Part IV

The timing of the death of Thomas Stevenson would have everything to do with the fate of his only child, Robert Louis Stevenson, whom he did not even recognize when the latter showed up next to his death bed at the family residence on Heriot Row in Edinburgh, Scotland.

On May 8, 1887, Thomas, who had been a solid Christian, gave up the ghost while sitting up in his bed with his pipe, the way he wanted it. As an inventor, he had written his own book defending his religion in the age of science and had often told his son that life is just “a shambling sort of omnibus taking him to his hotel.”

Stevenson had arrived in his hometown feeling “seedy” and with a cold. Too often, a cold preceded a visit from “Bloody Jack,” that being the invalid’s hemorrhaging lungs, a potentially lethal event every time. Consequently, his Edinburgh doctor who was also his uncle, Dr. George Balfour, forbade his nephew from attending the funeral. It was the largest private burial Edinburgh had seen up to that time, for a man who believed that dogs have souls and go to Heaven, too. While Louis stayed at home, he put the finishing touches on his ballad called “Ticonderoga–A Legend of the West Highlands.” This true story from the far side had been an active conversation piece between father and son.

The passing of Thomas was a milestone of course. There was nothing to keep RLS in the British Isles anymore. He was an only child and his mother would be joining him for whatever came next. She would be getting way more than she could have ever imagined. Dr. Balfour knew they all needed a change and suggested two options that had his patient’s best interests in mind. Go east and live in the foothills of the Himalayas for a good spell or go west to the American Rockies to do the same thing. It was an easy decision. The author’s wife, Fanny, was American and she was homesick. Colorado Springs it would be.

No, it wouldn’t. Most of the trans-Atlantic voyage to New York City aboard the steamship Ludgate Hill had been an absolute blast for Louis. Later on, he wrote about it to his cousin, Bob Stevenson: “I was so happy on board that ship, I could not have believed it possible … I have got one good thing of my sea voyage; it is proved the sea agrees heartily with me, and my mother like it, too …” That observation would be fundamental in Stevenson’s future plans.

Unfortunately, the fun came to an end and the suspense began again when Louis fell ill aboard ship with another cold about two days out from New York. On Sept. 18, from Newport, Rhode Island, where the Stevensons were guests of the Fairchilds, Louis wrote to his friend, Henry James, informing him that “I caught a cold on the Banks after having had the finest time conceivable and enjoyed myself more than I could have hoped.” The next day Mr. and Mrs. R.L. Stevenson went to Manhattan to see a lung specialist and plan their next move. Colorado was out — too far. The day after that, Sept. 20, the author’s mother gets a telegram in Newport and writes that very day to Alison “Cummy” Cunningham, Stevenson’s childhood nurse and dedicatee of “A Child’s Garden of Verses.”

“I have just heard that we are to go to the Adirondacks, a mountainous district not very far from New York. The climate is said to resemble Davos, and so may be just the thing for Louis.” Whoever that lung doctor was, he gets the credit for telling the Stevensons about Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau and the good reports they were getting about his new sanitorium on a mountainside near a backwoods hamlet that turned out to be closer to Canada than to New York.

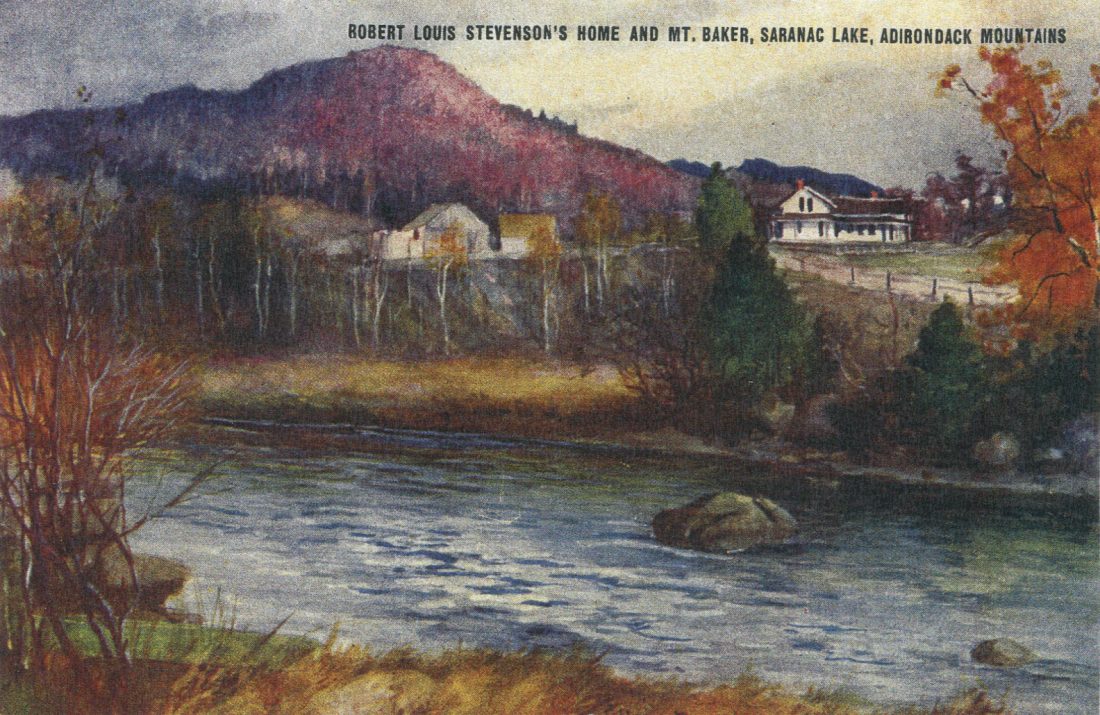

By early October, the Stevenson expedition had settled into their new winter quarters at their leader, RLS, wrote his first letter from there to cousin Bob. In it, he said, “The cold was too rigorous for me. I could not risk the long railway voyage (to Colorado).” So instead, “We have a wooden house on a hilltop overlooking a river, and a village about a quarter of a mile away.” The village was Saranac Lake, the river was the Saranac River and the house on the hill was “Baker’s — emphatically Baker’s.”

Saranac Lake did wonders for Stevenson because it was in the heart of the Adirondack ecosystem which thrives in and on a relatively thin layer of soil draped like a carpet over a recently uplifted mountainous mass of metamorphic rock that once formed the roots of a super ancient mountain range, the likes of which you can find at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, making the Adirondacks among the youngest and the oldest mountains in the world at the same time. A thin layer of soil with little or no clay is said to promote a drier climate which may be the secret ingredient that enables Saranac Lake to boast truthfully that these mountains, not just this town, are a healthy place to live.

In the first week of October, 1887, the members of the Stevenson expedition were discovering that for themselves. To get to Saranac Lake in those days, you had to go by horse and carriage from Loon Lake, over a mud and log road. Stevenson’s mother, Margaret, also “Maggie,” described the journey to her sister in Scotland by letter writing from Baker’s, “in my own room, which is very bright and cheery … At Loon Lake we found a nice buggy waiting for us; it had two horses and had been specially made for invalids, with good springs, which we fully appreciated while driving over twenty-five miles over very bad roads. The wind was cold, and when we were about half way the rain came on, and I was frightened about Louis…Fortunately he has been none the worse of the journey and the long drive in the rain, and says that he already feels the air of Saranac doing him good, so I trust we have hit on a place that will really suit him.”

The pre-eminent respiratory medicine Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau took on Stevenson and declared that his “illustrious patient” did not have TB after all. In his autobiography, Trudeau says, “Mr. Stevenson was my patient, but as he was not really ill while here I had comparatively few professional calls to make on him.” Trudeau did give the author advice though — quit smoking cigarettes and stay in Saranac Lake. It was an exercise in futility.

Stevenson’s wife, Fanny, wrote about the change, too. You can read this in the Stevenson Cottage brochure. It’s from a letter she wrote to a family friend in England: “He is now more like the hardy mountaineers, taking long walks on hill tops in all seasons and weathers.” One thing is certain. In Saranac Lake, Robert Louis Stevenson was anything but “a weevil in a biscuit,” the way he described his existence at his previous home in Bournemouth, England, the one where he wrote “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.”