Part I: RLS in Hawaii

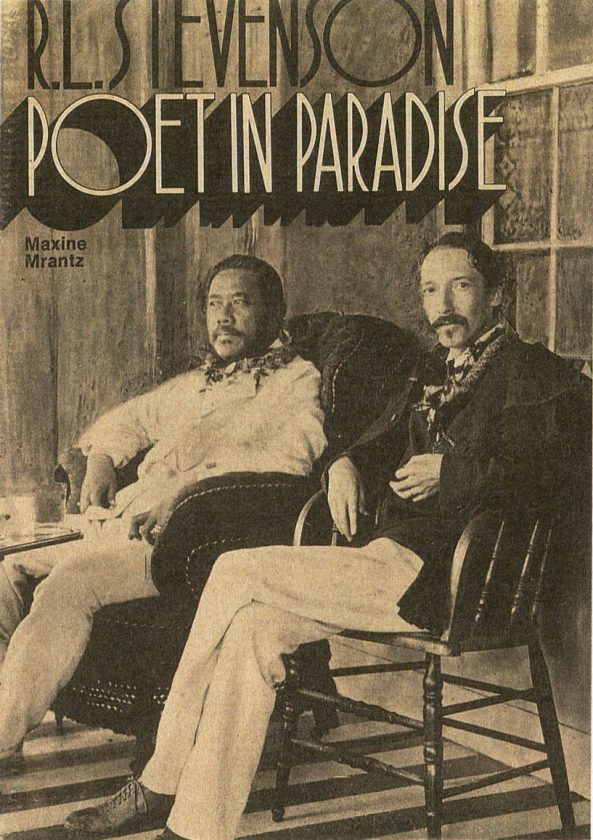

King David Kalakaua and Robert Louis Stevenson relaxing on the veranda of His Majesty’s Royal Yacht Club. (Provided photo)

“I know a little about fame now; it is no good compared to a yacht; and anyway there is more fame in a yacht, more genuine fame; to cross the Atlantic and come to anchor in (say) Newport with the Union Jack, and go ashore for your letters and hang about the pier, among the holiday yachtsmen–that’s fame, that’s glory — and nobody can take it away; they can’t say your book is bad, you have crossed the Atlantic.”

Robert Louis Stevenson to his cousin Bob Stevenson — Saranac Lake, October 1887

The books “Treasure Island” and the “Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde” are the two classic hits in English literature that had propelled this author with the initials ‘R.L.S.’ to fame by the time the creator of Long John Silver made Saranac Lake his home for the winter of 1887-88. With fame came more money than Stevenson had ever dreamed of earning with his pen for he was a modest man (for a genius) who downplayed his talent. He even felt guilty when he took $3,500 from Scriber’s magazine in New York City just before he came to Saranac Lake. “I am now a salaried party,” he writes to his critic friend, John Archer, in England. “I am to write a monthly paper for Scribners at a scale of payment which makes my teeth ache for shame and diffidence. … I am like to be a millionaire if this goes on, and be publicly hanged at the social revolution.”

But what to do with this money? Who hasn’t wondered what you could do if a modest fortune fell in your lap? Stevenson might have been thinking like that when he was writing his letter to Bob, because he concluded therein that “Wealth is only useful for two things — a yacht and a string quartette.” His wife, Fanny, would find the yacht — the Casco, Captain Otis, in San Francisco. Taking four musicians along on a voyage with his family and crew members was likely rejected as unmanageable, besides, Louis always kept handy his little silver penny whistle to bring into service whenever the urge to make music came upon him. This penny whistle was the first of many gifts to the Stevenson Society in Saranac Lake from the author’s stepchildren, Mrs. Isobel–“Belle”–Field and her brother, Lloyd Osbourne, when they joined it in 1916. It remains under glass at Baker’s to this day where it explains the title of the society’s little book, “The Penny Piper of Saranac — An Episode in the Life of Robert Louis Stevenson,” by Stephen Chalmers.

Sixteen months were to pass from the day Louis wrote that letter to Bob from Baker’s, the one in which he pictures himself hanging out with fellow yachtsmen in their fancy yacht club — “In (say) Newport”–to actually living that experience and in grander style than he had imagined. Instead of crossing the Atlantic, he had done the Pacific. Instead of any old yacht club, he was entertained at a royal yacht club as the guest of a king. “Stevensonesque” is a word often used to signify a certain effortless flair that seemed to be a feature of the RLS persona.

It was 3 p.m. on Jan. 24, 1889, when the Casco finally dropped anchor in Honolulu harbor after a difficult passage from Tahiti. First aboard to greet the voyagers were Belle Strong, Stevenson’s stepdaughter, and Austin, her boy of 7. On shore, they were joined by Belle’s artist husband, Joe Strong, and everyone walked to the nearby Royal Hawaiian Hotel for a feast of celebration. Belle features it in her book, “This Life I’ve Loved.”

“There were several guests besides ourselves, including Captain Otis. … During the talk at dinner, I noticed something I was to see often later on. A stranger had only to associate with Louis for a few weeks and ever after he would unconsciously imitate his odd twists of the English language and many of his mannerisms. Captain Otis gave a good example of this. When I had seen him last in San Francisco, during the outfitting of the yacht, he had been rather scornful, hardly disguising the fact that he had a very poor opinion of poets and writers. Now, at the dinner table he used many of Louis’ own expressions, copied his frank engaging manner and was evidently one of his warmest admirers. In telling of their adventures he was forever quoting Louis and bragging about his various exploits.” (Captain Otis is Captain Nares in “The Wrecker,” by RLS.)

“… My life changed completely with the coming of the Stevensons, and during the four months of their stay in Honolulu, I lived in a whirl of excitement and interest. The rambling picturesque old house they took on the beach at Waikiki was busy as a beehive; Joe Strong setting up his easel in one of the many rooms, worked as he never had before. My brother’s typewriter clicked as he tapped out revisions of ‘The Wrong Box.’ Aunt Maggie (Margaret, Stevenson’s mother) wrote letters and pasted references to Louis into one of her many scrapbooks (three of these are in the Saranac Lake collection). … Once I saw Louis turning over the pages of her latest one, and leaning over his shoulder, I asked: ‘Is fame all it’s cracked up to be?’ He thought a moment, then said, smiling: ‘Yes, when I see my mother’s face.'”

“… Though every member of the family was busy, the prize worker of them all was R.L.S. Waking at dawn, he would begin to write. While in Honolulu he finished ‘The Master of Ballantrae’ (begun in Saranac Lake, then running serially in Scribners magazine), worked with Lloyd over the last six chapters of The Wrong Box, composed five hundred lines of a narrative poem of Tahiti, sent off numbers of his South Seas Letters to McClure’s Magazine, besides keeping up with a mass of correspondence that had accumulated during his travels.”

Belle kept busy, too, at her stepfather’s ocean front residence: “An open door on the left framed a picture that I painted many times. Against a sky incredibly blue in the daytime, flaming with color at sunset, and most beautiful and impressive of all by moonlight, was Diamond Head … and there was nothing to mar the clean sweep of beach that cut a perfect semi-circle outlined by the foam of the waves.”

“… Though he liked seeing people, Louis complained that in Honolulu there were too many ‘haoles’ (whites — pronounced ‘howlies’). In one of his letters he wrote: ‘I don’t see enough of God’s best–his sweetest work–the Polynesians.'” Perhaps to correct that deficiency, RLS put his life at risk again by going on a solo tour of the Islands to gather material for a new project to be published with the title, “The Eight Islands.” The finished travelogue features the Kona Coast, the City of Refuge and his visit to the isolation station for lepers on the Kalawao peninsula on the island of Molokai. There the nuns at the Catholic Mission of the late Father Damien, mistook RLS for a tramp when he came seeking an interview with their boss, Mother Marianne Cope. “Well, he’s the best tramp I ever met,” said Marianne, “and the tramping he is doing here is not good for him as the poor man is subjected to hemorrhages.” Before returning to Honolulu, Louis spent a whole week living in the isolated hamlet of Ho’okena, a short distance from Healakeaua Bay where Captain James Cook and his party were killed on the beach by Hawaiian warriors. There Louis was the only white man — ‘haole’ — and he got his dose of “God’s best — his sweetest work — the Polynesians.”