Study: Most of Whitney Park too rugged for development

Analysis commissioned as part of lobbying effort for forest preservation there

- A posted sign at the bounds of Whitney Park land along state Route 30 is seen in the town of Long Lake on Dec. 12, 2024. (Enterprise photo — Chris Gaige)

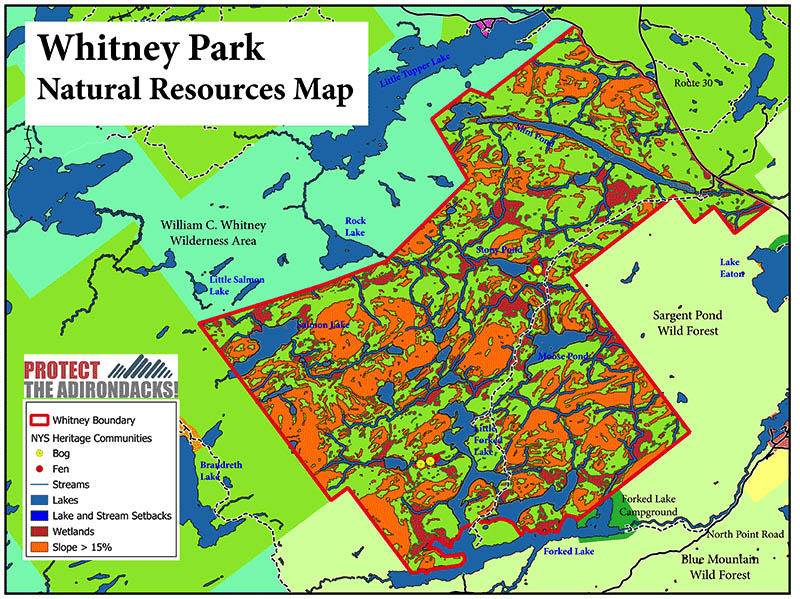

- A natural resources map depicting Whitney Park that was issued as part of a desktop study commissioned by Protect the Adirondacks!, claiming that much of the land, due to its rugged nature, would be difficult to develop. (Provided photo — Protect the Adirondacks!)

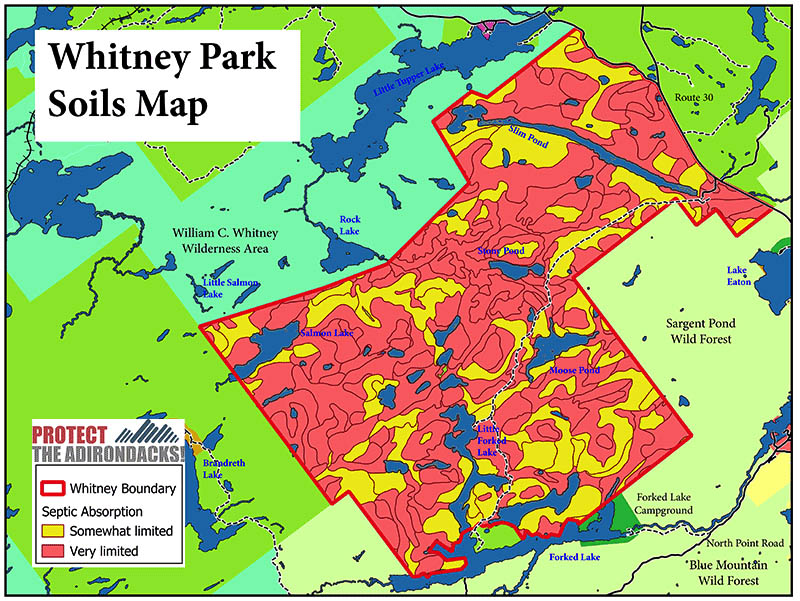

- A soil composition map depicting Whitney Park that was issued as part of a desktop study commissioned by Protect the Adirondacks!, claiming that much of the land, due to its rugged nature, would be difficult to develop. (Provided photo — Protect the Adirondacks!)

- A swath of land encompassing Whitney Park is seen during the warmer months from above. (Provided photo — John Hendrickson)

A posted sign at the bounds of Whitney Park land along state Route 30 is seen in the town of Long Lake on Dec. 12, 2024. (Enterprise photo — Chris Gaige)

LONG LAKE — Protect The Adirondacks! released a study on Friday, Dec. 12, claiming that much of the approximately 36,000 acres that make up Whitney Park would be difficult to develop due to either wetland status, poor soil composition, steep slopes or a combination of these.

It was a desktop study, meaning it used publicly available GIS and other mapping and natural resource data. It was completed by Steve Signell, of Frontier Spatial, a Vermont-based geographic data consulting firm. Signell has completed similar studies for Protect! previously.

Protect! is an environmental advocacy group that is opposed to the development of Whitney Park, which is currently up for sale in its entirety. The land was owned by John Hendrickson before his death on Aug. 19, 2024. Hendrickson had inherited it from Mary Lou Whitney, to whom he was married when she died in 2019.

The analysis found that Whitney Park contains 6,339 acres of lakes and ponds, 4,772 acres of wetlands and 748 acres of streams. This calculation includes a 100-foot shoreline setback area that the Adirondack Park Agency requires for structures on private land zoned under its “resource management” land classification, which Whitney Park is.

The analysis also found that 22,079 acres are at grades steeper than 7%. Of that figure, the study found that 10,458 acres have a greater than 15% slope. Protect! chose those figures because it found that golf course construction is significantly constrained on lands in excess of a 7% incline, as it said is the case for residential dwellings on land that has more than a 15% incline.

A natural resources map depicting Whitney Park that was issued as part of a desktop study commissioned by Protect the Adirondacks!, claiming that much of the land, due to its rugged nature, would be difficult to develop. (Provided photo — Protect the Adirondacks!)

In addition, it found that the soil characteristics are unsuitable for building site development, based on classifications from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.

It found that 22,821 acres are “very limited,” which Protect! said indicates that the soil is unfavorable for development and cannot be overcome without significant modifications, special designs and expensive installation and maintenance. In addition, it found that 10,610 acres are classified as soils that are “somewhat limited,” which Protect! said corresponds to soils that are moderately favorable for development but still require special planning, design or installation, and maintenance can be problematic.

“Nearly 95% of Whitney Park is either limited by wetlands, open water and steep slopes, or poor soils that cannot support development,” Protect! Executive Director Claudia Braymer said in a statement. “This natural resources analysis makes clear that Whitney Park should not be developed and must be protected.”

Protect! has not yet taken a position on whether the current great camps and other structures on the property, most notably Camp Deerlands and Camp Togus, should be demolished for subsequent addition to the Forest Preserve, or preserved separately from Whitney Park’s vast undeveloped areas.

Protect! has been “very involved” in lobbying for the state to purchase the land for preservation, according to Braymer. She said Protect! wanted to make the study as complete as the data — which was gathered through the state GIS Clearinghouse and U.S. Geological Survey — would allow, while making the maps readily understandable for a general audience.

A soil composition map depicting Whitney Park that was issued as part of a desktop study commissioned by Protect the Adirondacks!, claiming that much of the land, due to its rugged nature, would be difficult to develop. (Provided photo — Protect the Adirondacks!)

“We’ve wanted to gather as much information as we can about the natural resources on this site, and make a really good case to the governor about why she should be expending state resources for this particular piece of property,” she said.

Braymer added that Whitney Park has been in the state’s Open Space List since its inception in 1992, and before that, conservationists and other environmental leaders had been eying it as a priority to add to the Forest Preserve, given its centrality in linking surrounding wild lands and waterways.

She said that in the future, Protect! would like to gather more information on the land’s ecological value through on-site surveys, but has not yet approached Hendrickson’s estate for permission, given that Whitney Park is posted private property.

On-site data could include wildlife surveys, water quality sampling and wetland delineations, Braymer noted.

“We know there’s really good loon habitat, which is important,” she said. “There could be species, endangered species or other threatened species on the property that nobody knows about yet — which we may not be able to know until scientists are able to get access to the property.”

A swath of land encompassing Whitney Park is seen during the warmer months from above. (Provided photo — John Hendrickson)

–

Regarding the sale

–

Hendrickson’s estate is overseeing the property’s listing. It’s currently on the market for $125 million. Braymer thought that Protect!’s study results point to it being an overvalued listing, given how difficult the analysis suggests much of the property would be for future development.

In his will, Hendrickson was adamant that he did not want the state to acquire the land because he was upset by what he saw as poor stewardship by New York of other land that he and Mary Lou Whitney had sold to the state previously — much of what makes up the roughly 19,500-acre William C. Whitney Wilderness area, bordering Whitney Park to its north.

William C. Whitney was the grandfather of Cornelius “Sonny” Vanderbilt Whitney, to whom Mary Lou Whitney was married at the time of his death, when the land was passed to her. William C. Whitney had purchased vast tracts of land throughout the late 1800s in the central Adirondacks — about 80,000 acres — with much of that having been sold off over the years.

Hendrickson’s will also instructed that proceeds from the land’s eventual sale be given to the town of Long Lake, a community that the Whitney family cherished and had made extensive philanthropic contributions to over successive generations. More on that legacy, and gift to the town, is available at tinyurl.com/mvmczeu4.

Earlier this fall, it appeared Whitney Park had a strong chance of selling at close to its full asking price. As first reported by James Odato, of the Adirondack Explorer, a private developer named Shawn Todd, through his company, Todd Interests, was in serious discussions with Hendrickson’s estate, and the state Department of Environmental Conservation, over the purchase.

It appeared as though Todd Interests could front the purchase, but subsequently wanted to offload the vast majority of the land there — about 32,000 of 36,486.7 acres up for sale — to recoup much of its initial expenditure. From there, it appeared as though Todd wanted to develop the remaining 4,000 acres — that would be situated around Camp Deerwood and Camp Togu — into a resort and club, with a set of golf courses and lodging accommodations. Todd had hoped the state would be able to purchase those 32,000 acres for preservation.

The deal, however, fell through when it became clear that Hendrickson’s estate would not allow Todd to resell the land to the state. A last-ditch offer was made where the state could purchase a 200-year lease for the 32,000 acres, and manage it similar to how it would if it were part of the Forest Preserve — though it could not be formally added to it, given the Forever Wild clause in the state constitution governing these lands.

In a letter published by the Explorer, Todd said he personally had no qualms about selling land to New York, but that this lease was the only clear path that Hendrickson’s estate would allow him to offer. Ultimately, the state rejected the lease, deciding it wasn’t worth purchasing an agreement short of outright ownership.

With the state’s rejection, Todd said it was no longer feasible for him to purchase the property, but that he could re-engage should the estate or the state’s terms change in the future. Odato reported there was a difference in interpretations of Hendrickson’s will between Hendrickson’s representatives and Todd. The trustees said the language is clear that future owners cannot later sell it to the state. Todd contested that it only concerned who the trust could sell the land to, not future owners.

It’s unclear if there is, or will be, a formal deed restriction for the property precluding state ownership — which could be tied to the land in perpetuity, regardless of individual owners. It’s also unclear what Hendrickson’s will actually states, as it has not been publicly released.

“We would urge the trustees to make the information public so that everyone can see and read it for themselves,” Braymer said. “I think it’s a really important question, and with this piece of property being in the public eye so much, it would make the whole transaction a lot clearer and quicker if people knew exactly what the language was in the trust document about the deed restriction.

“Does it really restrict the state from purchasing here initially?” she added. “Or, are they really trying to put in a deed restriction for perpetuity because that’s what’s in the trust, or because they thought that’s what John Hendrickson wanted? Which, I think, are two completely different things from a legal perspective.”