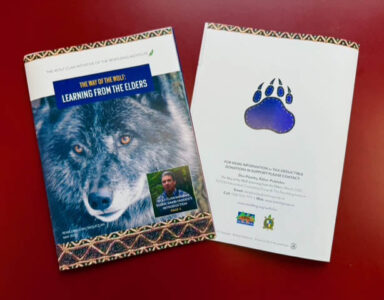

‘The Way of the Wolf’

- The first “Way of the Wolf” publication from the Wolf CLAN Initiative. (Provided photo — Dan Plumley)

- David Kanietakeron Fadden, a Mohawk Wolf Clan member and contributor to the Wolf CLAN Initiative, which seeks to support the return of wolves to the Adirondacks. (Provided photo)

- Dan Plumley, a co-founder of the Wolf CLAN Initiative, which seeks to support the return of wolves to the Adirondacks. (Provided photo — Dan Plumley)

The first “Way of the Wolf” publication from the Wolf CLAN Initiative. (Provided photo — Dan Plumley)

ONCHIOTA — David Kanietakeron Fadden wants to hear his cousin. He’s a member of the Mohawk Wolf Clan through his mother, but he’s never seen or heard his clan’s namesake in the wild.

Wolves were once common throughout the Adirondacks and New York state. Human hunting and deforestation killed them and drove them out long before he was born and the last wolf may have been killed in the late 1890s. Fadden said it’s probably been three generations or more since a member of his family heard the yips and cries of the his cousin, “Okwaho.” But there’s always been rumors of wolf sightings around the woods from time to time.

The state Department of Environmental Conservation recognizes three confirmed wolves in the state since 2001.

Recently, Fadden wrote for the inaugural edition of a new non-profit initiative’s publication “The Way of the Wolf,” an introductory 18-page booklet co-authored by native and non-native advocates writing about wolf restoration and protection.

The Wolf CLAN “Wolf Canid Life Advancement Nation” Initiative, hosted by The Rewilding Institute, is focused on protecting and conserving wild Eastern and Gray wolves and their habitats. The Rewilding Institute is a federally recognized environmental non-profit based in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

David Kanietakeron Fadden, a Mohawk Wolf Clan member and contributor to the Wolf CLAN Initiative, which seeks to support the return of wolves to the Adirondacks. (Provided photo)

Environmentalists and Wolf CLAN co-founders Dan Plumley, Joseph Butera and John Davis, along with Fadden, wrote for the first edition of “The Way of the Wolf,” titled “Learning from the Elders,” on the power and aura of the wolf, as well as the state of their protections.

There are numerous groups supporting wolves. Plumley said this one focuses on sharing native voices, something he feels has been missing in the movement.

The initiative aims to form a “nation” of wolves, activists, Native American leaders, scientists, politicians and educators from Canada and the U.S.

Right now, with the introductory publication, the initiative is focused on making connections. This is a starting point.

Fadden grew up in Onchiota, where he still lives and operates the Six Nations Iroquois Cultural Center. He developed a deep connection with the natural world by walking around the woods and observing as a child.

Dan Plumley, a co-founder of the Wolf CLAN Initiative, which seeks to support the return of wolves to the Adirondacks. (Provided photo — Dan Plumley)

“One only has to walk 20 feet into the forest and realize that this place in teaming with life,” Fadden wrote.

He heard, saw and observed signs of an array of animals — but never a wolf. They are a member of his family he has not met in the wild yet.

The Mohawk “Ohen:ton Karihwatekwen,” or “Thanksgiving Address,” is spoken at all gatherings “to remember the place humans have in the larger fabric of the world family.”

“The Earth is our mother, the sun is our eldest brother, the moon our grandmother, the thunders are our grandfather and the animals are our cousins,” Fadden wrote. “When one looks to and considers these entities as members of our family, we tend to take care of them. This is how we look to our cousin, the Okwaho (wolf).”

Today, many people do not have this oneness with their surroundings, he said. Cement and technology have separated the two and Fadden said many people feel no kinship when wolves are discussed.

To read an online version of “The Way of the Wolf,” go to rewilding.org/wolfclan.

The publication is dedicated in memory of Alan “Anataras” Brant — a Wolf Clan Mohawk, Iroquois environmental activist and traditional educator from Ontario, who died last year, His daughter, Tsiokeriio (Diio) Hagen, produced the bead art which adorns the cover pages of the publication.

–

Wolf comeback

–

Wolves are migrating back into the Adirondacks. Not enough to have a breeding population yet, but with enough frequency to excite advocates. They mostly come from across the St. Lawrence River and from the Great Lakes area, advocates said.

The Adirondacks are 300 miles from Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada, which has one of the largest wolf populations in the East. Butera camped there numerous times and said the topography of that park is almost identical to parts of the Adirondacks.

The Algonquin to Adirondacks Collaborative is dedicated to keeping the “A2A corridor” between the two parks open to wildlife and free from human development.

Plumley said these wolves need habitat connectivity to allow for roaming and migration in this transboundary region.

Most of the time, wolves are only confirmed to have been in New York after they’re dead.

In 2021, Butera was part of an effort to get DNA testing from a wolf shot near Cooperstown, which was initially thought to be a coyote. DNA from the canid showed it was indeed a wolf, and had traveled around 1,100 miles from the Great Lakes region.

Most wolves migrating here are solitary “omegas” who leave their packs for new terrain, Plumley said. In the winter of 2023-24, he tracked a suspected wolf in his hometown of Keene. He said the stride and paw-prints were twice as large as that of a coyote, and he spoke to four eyewitnesses who testified that the canid was significantly larger than a coyote.

Plumley said wolves get confused for coyotes here because eastern coyotes are bigger than they are in other regions. Eastern coyotes have a bit of wolf genetics through cross-breeding.

In the 1960s, Butera recalls his friend’s father trapped what he believes were two wolves. There weren’t supposed to be wolves in the Adirondacks at the time, so no one ever looked into it, but he said they were too big to be coyotes.

In the last 30 years, a number of wolves have been killed in the Northeast by hunters hunting coyote. Some of these cases are documented, some come by word of mouth.

Butera is part of a small group of advocates working to document these cases — they collect scat and hair from the forest, get DNA testing from the bodies of large canids harvested by hunters and set trail cameras in areas people report hearing wolf-like howls.

Before the state Legislature’s session ended in June, legislators had proposed a wolf protection bill which would require any canid larger than 50 pounds killed by hunters to be DNA tested by the state, to see if they are wolves. Plumley said this comes from a desire for accurate knowledge.

–

Perception

–

As wolves migrate back into the Adirondacks, advocates said they need certain things to survive — things like land and food, which are plentiful here.

What do they need most?

“Not to be shot,” Fadden said.

He said they need protection from the new apex predator of the Adirondacks — humans.

Indigenous people hunted here for many, many years, but they did it out of necessity.

“It’s not a sport to kill an animal,” Fadden said.

He said they didn’t overhunt and they didn’t clear cut the trees. Onchiota was clear cut at one point, potentially twice. He added that hunting and logging are supposed to be sustainable, not exploitative, with future generations in mind.

Wolves are protected on both the state and federal lists of endangered species. Plumley said their addition to the list was “controversial” at the time.

“That goes with the territory for predator species,” he said.

Fadden said there’s long-entrenched views of wolves that skew how they are perceived, different that the native view.

“European stories depict wolves and the natural world in their traditions as something to be terrified of and conquered,” Fadden wrote. “The notion that this earth is here for mankind and that we shall have dominion over nature is not only foolish, but dangerous.”

But Native Americans see the wolf as family.

The difference can be seen in some of the most formative media — children’s stories.

In Europe, Fadden said most wolf stories were “Big Bad Wolf”-style tales. Still to this day, most depictions of wolves in media are of snarling, evil-looking canids.

In Indigenous oral traditions, animals have human traits. Fadden recalls a children’s story of a man who raises two orphaned wolves from pups. One day, when he is hunting in the mountains, an evil creature called a “flying head” attacks and the wolves sacrifice themselves so he can survive.

Fadden said clan members are said to take on their clan animal’s attributes. Wolves are known for their family loyalty, caring for children and elders and deep communication abilities within their packs.

“You learn that through observation, not observation through the scope of a gun,” Fadden said. “There are these personal qualities attached to these animals. They’re not to be dominated, not to be destroyed or killed.”

People have been a taught fear of wolves, Fadden said. He understands that fear, but said they don’t know the full story. When people only hear bad things about a group, they fear them. Humans do this to other humans, too, he said.

If wolves are to reestablish themselves in the Adirondacks, he said humans need education, to understand the rules of “don’t disturb them and they won’t disturb you.”

–

Keystone species

–

For decades, researchers have identified the Adirondacks as having a high potential for a wolf habitat. It has large swaths of protected wild lands free from human intrusion. There’s also an “overabundance” of white-tail deer and white-footed mouse here. This is largely because the Adirondack ecosystem is missing its top predators, such as the wolf. Coyotes aren’t deer-killers in the way wolves are.

Butera said the wolf is a “keystone species,” one which ecosystems evolve around, and whose survival is essential for other species.

Coyotes are not native to the East. They moved in from the West after the wolf population here was killed off. Wolves suppress coyote numbers because they are competitors for food.

Butera believes that if wolves returned to the East in large numbers, Lyme disease would decrease dramatically.

The rise of white-footed mice and white-tailed deer following the loss of wolves and other predator species has been cited as a contributing factor to the rise in tick-borne diseases in the East, because deer and particularly mice are vectors for ticks. Plumley said the Adirondacks are missing a key component of its biological system without wolves.

When deer ticks are born, they don’t carry diseases. They acquire them from biting infected animals like mice, and then share those illnesses with humans.

“There’s nothing that eats mice like red fox. Coyotes see red fox as competitors for food, so coyotes will try to kill red fox and kill their pups,” Butera said. He then explained what he believes would likely happen if wolves were restored to the Adirondacks. “Wolves kill coyotes. Coyote population goes down. Red fox population goes up. Lyme disease goes down.”

Wolves can even impact trees. When the last wolf was killed in Yellowstone Park in 1926, ash trees stopped growing and didn’t return until wolves were reintroduced in 1995.

“It was about the fear factor that wolves inflict onto their prey species,” Butera said. “It keeps them moving — like elk and moose and deer — so that they’re not sedentary, just eating everything constantly.”

Butera said the first law of ecology is “Complexity brings forth stability.” Essentially, a diverse and interconnected ecosystem allows it to withstand negative effects. If predators are removed from that system, other species die out.

“We f****d this place up, this place Earth,” Butera said.

Though he doubts it will happen in his lifetime, Fadden said he believes wolves may make a home in the Adirondacks, if humans allow.

“It is my sincere hope that someday a young Wolf Clan Mohawk will, once again, hear the song of our cousin, the wolf,” Fadden wrote.