Back to Baker’s, Part I

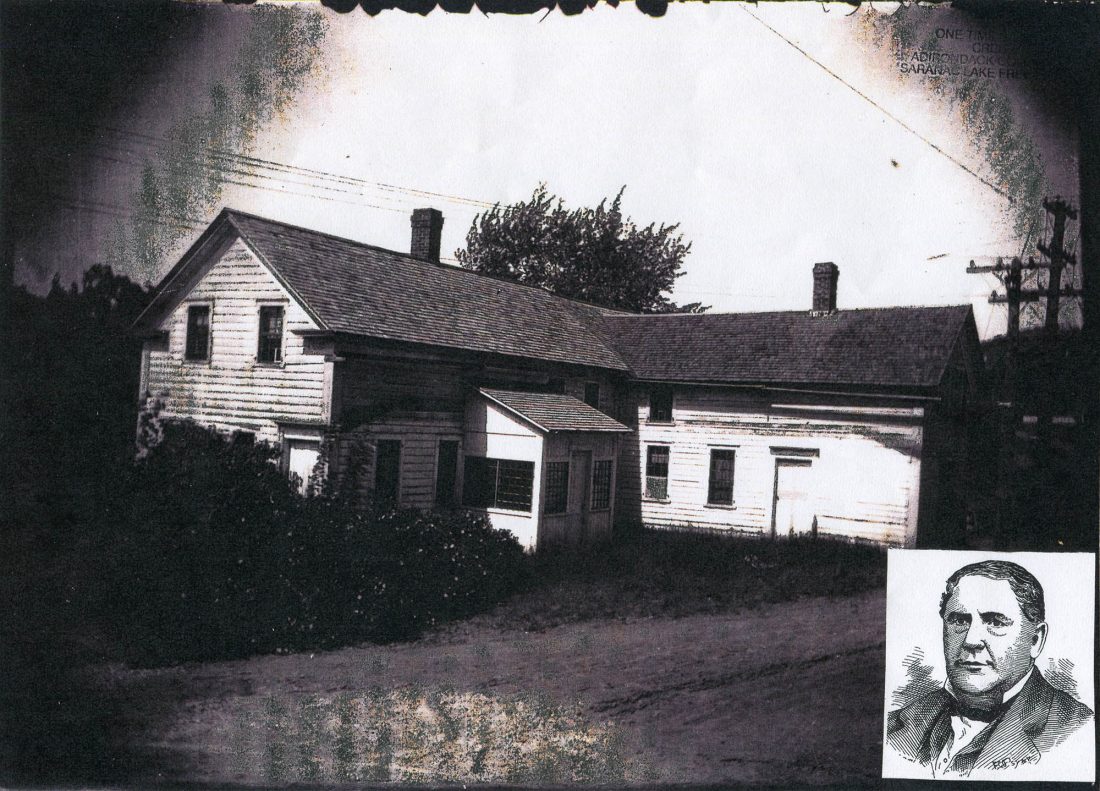

“Baker’s Tavern,” as it appeared in the 1920s shortly before its demolition. Col. Milote Baker (inset) officially named this settlement Saranac Lake, in 1854, for the U.S. Post Office he had built inside his store on present day Triangle Park. (Photo provided)

(This week begins a new section of this series which will feature the legacy of the Baker family and the formation of the Stevenson Society of America.)

In the spring of 1852, Colonel Milote Baker, 46 years old, crossed the first bridge over a section of the Saranac River near some rapids. When he got to the other side, the colonel could have pointed east and told anybody with him that “this is all mine!” The Saranac River was the western boundary of a 600-acre chunk of real estate he had recently legally purchased. It was about one half of a rectangle on a map called “Lot No. 11.” Baker’s wilderness domain included a mountain for a centerpiece with an inviting pond at its base. He would have to come up with a name for his mountain. Coming “Up the River” to settle in a remote mountain valley was a big change from Baker’s previous employment, running the commissary at Sing Sing Prison on the Hudson.

Milote Baker was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts, in 1806. As a young man he decided to go west. He got as far as New York State. Baker earned his military rank by joining the New York State Militia. After leaving Sing Sing, Baker re-invented himself. He did it by building a hotel in the middle of nowhere, a three-day trek in 1852 from the nearest imitation of civilization, Plattsburgh, New York, the starting point for people coming “Up the River.”

When Col. Baker came here, this last settlement on the river was still occupied by its two founding settlers. Jacob Moody got here first, in 1819. Following an injury in a saw mill, Jacob got it in his head to follow the Old Military Road north from Elizabethtown, until he found a location that suited him to start a farm after building a log cabin. That farm was somewhere in the vicinity of the present day NBT Bank and nearby former railroad crossing. Inside his cabin, his wife brought forth four sons to help him do the work: Cortez, Daniel, Martin and Franklin. All four married and had large families so the Moodys are still among us. Jacob Moody died in 1863.

Captain Pliny Miller, a War of 1812 veteran, showed up in this area around 1822. By 1827, he had acquired 300 acres of land which included much of present day downtown. It also included a 10-foot waterfall. Miller built a dam there which turned the terrain behind it into Lake Flower and Miller Pond. Next, he built a sawmill off the dam which was a profitable project. New pioneers looking to settle could buy both land to build on and lumber to build with from the Captain. The clapboard buildings along proto-Main Street in the oldest village photos, were the products of such transactions.

In this way, the Millers were more consequential than the Moodys when it came to the transition of this settlement into a hamlet which was still called “Up the River” when Col. Baker came up it to settle. According to Alfred Donaldson, this triumvirate of founding settlers–Moody, Miller and Baker–are the pioneers of distinction, the ones most worthy of inclusion in his classic History of the Adirondacks.

Col. Baker’s gamble paid off. He built his hotel in the middle of nowhere and people came. Having a bar there helped. Paul Smith did the same thing at Spitfire Lake. There were more like them, entrepreneurs planning to cash in on the wave of tourism they knew was coming this way. The Adirondack region, long ignored, had finally been discovered in the 1840s by the east coast city populations. It was during the period of social upheaval caused by the Industrial Revolution and a return to Nature was the theme of the times, the so-called “Romantic Era.” The Adirondack region was well situated in place and time to meet the need.

Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau was a product of this movement. He was in his care-free, disease-free, spoiled rich kid stage when he and two of his peers summered at Paul Smith’s hotel, running up a bill that didn’t worry them either. While the white man’s attraction to these mountains grew, so did the grief of the Native American tribes who surrounded them. Up until then, these mountains were their sacred hunting ground, a pristine wilderness since the retreat of the glaciers, a holy place.

As for Col. Baker, Donaldson says that “The colonel was a man of commanding presence, with a tinge of the aristocrat in his manner and bearing. He came indeed of old New England stock … He was a good talker and genial companion, who paid his way socially, and enjoyed mixing with the distinguished people who lodged beneath his roof…He had, in short, little of the typical pioneer, except a fine physique and prodigious strength, which he did not hesitate to use on occasion.”

Col. Baker had four children by his first wife, Miss Susan E. Roberts. The first three were his daughters Narcissa, Julia and Emma. Then came the colonel’s only son, born in Keeseville, New York, in 1841, and named after Baker’s favorite hero, Andrew Jackson. Andrew Jackson Baker began his career by growing up like any normal backwoods kid would have. He lived in the residential part of his father’s backwoods hotel which sat on the bank of the Saranac River, in which he learned to fish. His family owned hundred of acres of virgin Adirondack forest in which Andrew learned to hunt. By the time he was fourteen, Andrew had perfected his survivalist skills and began hiring himself out as a professional guide to the paying guests at “Baker’s Tavern.”

Besides whatever rural schoolhouse education he achieved, Andrew went in for higher learning when he enrolled at Fort Edwards Institute in Fort Edwards, New York. His graduation autograph album which is in the museum collection, must have every name in it from his class of February, 1863, two months after Fredericksburg.

In 1866, Andrew went to Michigan to marry his fiancee, Mary Scott, daughter of a Michigan State legislator. Their rather large, framed marriage license is still hanging in the house on Stevenson Lane that they called home for 58 years. When Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Baker returned to Saranac Lake, Col. Baker gave them the quaint, two-story cabin that sat on a knoll a short distance east from his tavern. Baker had built the cabin in 1855 for one of his employees, Ebenezer Griffith. By 1866, Ebenezer had moved on, one way or another, so Andrew and Mary moved in for whatever the future might have in store.

Andrew Baker proceeded to build off the cabin on the north and south sides, giving the Cottage its present-day appearance from Pine Street. He bought his lumber from Miller’s sawmill and got nails, paint and other necessities from Cortez Moody. Andrew kept a notebook recording all his construction purchases starting in 1866. It too, along with other records of historical interest, is in the museum collection.

The home Andrew was building in 1866 for his wife and family-to-be was a farmhouse because he also built a farm around it, complete with corn fields and chicken coops and livestock and a classic Adirondack farm that managed to survive until 1986; however, the primary income for the Bakers came from Andrew in his role as a professional Adirondack guide. Now, with a wife and kids planned, it only made sense to move his business from his father’s tavern to his cabin expansion project. Putting in a fireplace had not been in his plans. Alfred Donaldson gets the last word:

“Strange as it may seem, open fireplaces were a late and rare luxury in the Adirondacks. The one in Andrew Baker’s home was suggested by Mr. Riggs, of Riggs Hotel in Washington D.C. This gentleman was among the regular summer visitors at Baker’s Tavern, and when he heard that his favorite guide was going to build a house and take boarders, he urged the open fireplace and agreed to pay half the expense of constructing it. After it was built he sat before it on many a chilly night–as did Robert Louis Stevenson after him.”

To be continued.